Where’s The Spark?

Part I – Part II will be out on Monday.

My daughter turned 50 on September 4, and today we’ll host a garden party in her honor with about 40 guests. It’s not a potluck, we’ll provide lots of yummy vegan dishes, from Thai Basil Eggplant stir fry and Soba Noodles with peanut dressing to lentil salad, pizza, vegan no-sausage rolls, zucchini chips, and orzo-stuffed tomatoes. The birthday cake is a vegan Tiramisu. All this to say that I’ve been busy cooking the last few days, with hardly a minute to spare for anything else – sorry for this piece-meal post!

After I wrote my last piece about Degenerate Art, the name the Nazis gave to paintings, sculptures, literature, music, and anything else they deemed un-German, un-natural, un-decent, and the exhibition by the same name which displayed some of the greatest works of modernism, I couldn’t stop thinking about all the “-isms” that influenced culture at the time. I’ve always loved Expressionist art so I focused on some of its painters last week, but there was so much more going on in the early part of the 20th century.

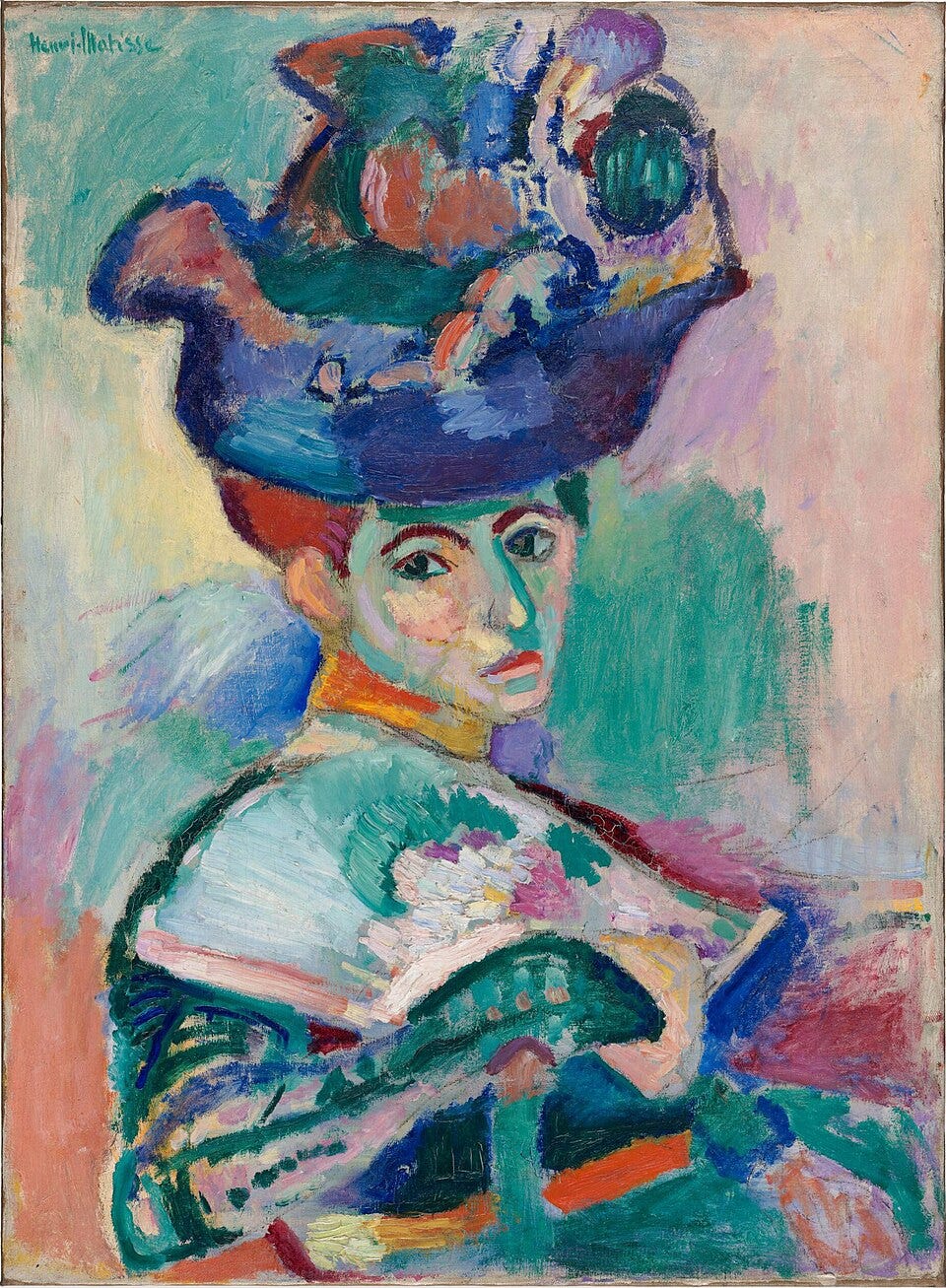

There was Fauvism, prominent in France, spearheaded by Henri Matisse. Other painters associated with Fauvism were André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Robert Delaunay, and many more. After their first show at the annual fall art exhibition in Paris, Salon d’Automne, their bold use of bright colors and thick brushstrokes caused critics to compare them to "wild beasts”, fauves in French. While this was meant as derogatory sneer, the artists proudly embraced the notion of being wild.

Georges Braque, who started out as a Fauve, went on to develop Cubism, parallel to Pablo Picasso. The highly influential style did away with a three-dimensional rendering of its subject and added different viewpoints from different angles set together on a two-dimensional plane. Again, the name initially stemmed from a negative comment: French art critic Louis Vauxcelles wrote that Bracques reduced everything to cubes, and called the paintings “cubic oddities”.1

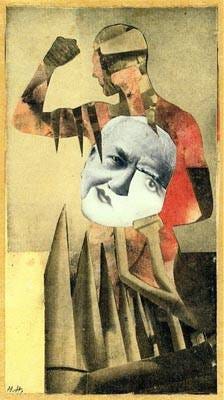

Dadaism was deliberately anti-establishment, protesting war (it started in 1915, one year after World War 1 began), nationalism, modern capitalism, conservatism, and was meant as an “anti-art” movement. It quickly spread from Switzerland to Berlin, Paris, New York, and other artistic centers in Europe and Asia. Its most famous protagonists were Jean Arp, George Grosz, Marcel Duchamp, Raoul Hausmann, and very few women – interestingly, these avant-garde men were somewhat misogynistic and allowed female artists only begrudgingly to be part of the group. The painter Hannah Höch, for example, was the only woman in the Berlin Dada group, and her male colleagues tried hard to get rid of her.

Surrealism emerged from and followed Dadaism. Its protagonist was André Breton who published the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. In it, he explains his take on realism (which he finds constrictive and boring), and his understanding of Sigmund Freud’s theories (who he met in Vienna in 1921). Dreams and the subconscious from which they arise fascinated him – to free himself of the perceived restrictions of the conscious mind, he invented a method he called automatism, or automated writing. It’s a technique which allows thoughts, images, feelings etc. to be recorded without the intervention of a judging consciousness. Supernaturalism, a state of mind that validates dreams AND reality, became Surrealism. Because of his charisma, Breton’s influence grew quickly and his ideas were taken up by artists, composers, choreographers, philosophers, film makers, and also involved politics – he joined the Communist Party for a while, became disillusioned and quit. But he met Trotsky in Mexico.

I’ll continue with Existentialism on Monday, and the lack of …isms in the 21st century – except, Gawd forbid, Trumpism?

Great summary of that creative time, so much spurred by the War and the Spanish flu which caused people to really question their reality, a lot like today. Thanks Jessica.