Some of my earliest childhood memories are stories, told by my father’s older siblings at the regular family gatherings. Every Sunday afternoon my aunts and uncles, my parents, and my six older cousins would get together at my grandparents’ for coffee and cake, a German tradition. The grown-ups shared stories from the war: how the air raids would wake them up in the middle of the night, how they had to grab their kids and run to the bomb shelters. How they listened anxiously to hear whether there was a loud explosion nearby, how they worried whether their house would still be there, how hard it was to calm the children who were afraid and crying.

I was born in May of 1946, so I didn’t experience any of that. But the stories shaped who I am today. My mother was born and grew up in Austria; she met my father because he went to medical school in Graz where she lived. They got married in the spring of 1945, and when Germany surrendered and the war ended, any Austrian who was married to a German citizen had to leave the country. My father worked at a field hospital at the front somewhere in Russia (all young German men had to join the army, but he often said how grateful he was that he never had to kill anybody. This was one reason why he became a doctor, and I loved him for it). I don’t really know why, but he wasn’t there to help her when my mother had to leave Austria. She was allowed to bring two suitcases, but they became too heavy during the long train ride and she left one behind – half of all the stuff she thought was absolutely essential.

Another early childhood memory: “Don’t play with a bomb if you find one!” Grown-ups told us kids again and again. Apparently, there were live bombs in the rubble, some detonated and seriously injured or even killed children. It was at least 50 years before I realized that I had no idea what they looked like when I was little; I guess I was simply lucky that I never came across a bomb.

Oh, and the rubble: there were several bombed-out houses on the street where I lived. Tempting places for kids to explore, but again there were serious admonitions: “Stay away. DON’T play there”. Floors could collapse, walls could crumble, half-broken ceilings could cave in.

Once I was a bit older, early school-age I think, I tried in vain to imagine what it must have been like to live through years of war and bombings. How could they have endured this? When I was 12 or 13 or so and had learned about the Holocaust, the question changed: “How could you have let this happen?” I didn’t get any satisfying answers, ever. Which is as it should be; some questions need to be kept alive and asked over and over again.

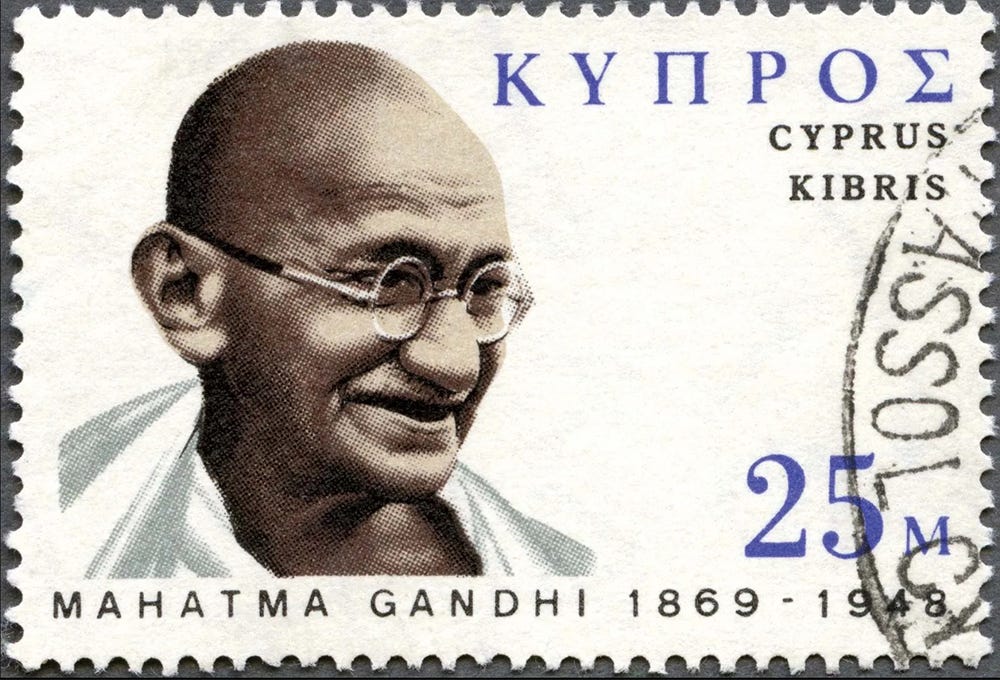

The stories I heard when I was little firmly instilled a permanent horror of anything connected with war: armies, uniforms, weapons, guns, air raid sirens, bombs, gas masks, whatever else even remotely related. When I protested against the war in Vietnam I had heard of Gandhi; he was promoting peace, I thought. And I knew that he had achieved India’s independence from British rule with nonviolent means, but I had no clear idea what this was all about. I didn’t know, for example, that Gandhi’s concept of Satyagraha, nonviolent resistance, was inspired by the writings and beliefs of Leo Tolstoy who had written A Letter to a Hindu In 1908. The way for India to gain independence from colonial rule was through the law of love, Tolstoy wrote: nonviolent protests and other forms of peaceful resistance should be the means to reach liberation rather than violent revolution.

Gandhi, who was living in South Africa at the time, read the letter after it was published in an Indian newspaper. He wrote to Tolstoy, asking for permission to reprint the letter in his own newspaper, and this led to a correspondence between the two men which strongly influenced Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha – his tactic of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance. It’s sometimes called “passive” resistance, which is a total misnomer – there’s nothing passive about it, as I learned when I studied the Civil Rights Movement and read John Lewis’s biography, Walking with the Wind.

When I joined the student protests and counterculture movement of the late 1960s I thought I was pretty active. I lived in a commune in Munich, together with some of the leading figures of the German protests; Fritz Teufel was one of the four other commune members. Instead, as I realized much later, I was RE-active. The police violence that I experienced, the injustice that I saw metered out to friends, drove me more and more to destructive acts: “If I get punished for doing nothing bad, I might as well do something bad next time”. This was a dangerously escalating spiral and I didn’t see the cognitive dissonance: on the one side I was for peace, against killing, and I hated violence, on the other hand I came recklessly close to committing violence myself. It was sheer luck that I ended up in India instead of a training camp in Jordan and eventually in jail or dead, as some of my friends. Actually, I think it was thanks to my Guardian Angel.

What nonviolent resistance really means I learned from reading John Lewis’s book. He became chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) after he attended workshops on nonviolent direct action. He and his fellow students joined sit-ins at lunch counters in establishments with strict segregation, practically everywhere in the South. He was one of the Freedom Riders in 1961 protesting segregated buses; they encountered mob violence and risked their lives on top of being arrested. And he led over 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama on March 7, 1965 where he suffered a fractured skull and thought he would die.

Lewis called these actions “Good Trouble”, and in his biography he explains what they necessitate. He and fellow SNCC members practiced their nonviolent response to being attacked. Far from being passive endurance, it required the inner development of love – yes, LOVE. For the Enemy, the Other, the Adversary. The person who hurt you, spit on you, wants you dead. I understand the words, but am miles away from embracing the concept. When I read the news I come across tons of people who I despise and have nothing but negative feelings for. And yet – in the face of today’s wars and protests and politics, maybe it would be the right thing to practice nonviolence in the tradition of Gandhi and John Lewis. Satyagraha means Truth-force, or Love-force, and it believes that there is more to human beings than simply a brute nature. Maybe this is something to strive for.

I have a beloved t-shirt that says “Good Trouble”. And I adore John Lewis.

Jessica, your light is shining brightly here in the algorithmic world. I think of you as a beacon, a lighthouse if you will. Sometimes a danger alarm. Most times a guide for those of us in need of truth and comfort. I cherish our connection.

♾️❤️😘✌️♎⭐💙♾️

i was very into the non-violent movement when i was younger / very influenced by gandhi and martin luther king jr / thoreau also / that eventually evolved into a less idealistic but more practical approach - finding personal peace / light my candle so to say and if there is another candle light around light that one too / none of the political revolutions will work until people light their candles / that's what i think