In my mother tongue, German, the word for “soil” is the same as for “Earth”, Erde. As in Pearl S. Buck’s novel, The Good Earth. I always find it a bit grating when people call it dirt, which is a substance that soils your shirt, makes it dirty, according to the dictionary.

Or, one can look at earth or soil as being one of the four elements, with water, air and fire being the other ones. The pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Empedocles developed the concept of the four elements in the 5th century BCE, claiming that all matter in the universe was composed of these four fundamental, immutable, eternal elements which he called “roots”. Chinese philosophy has a similar concept, Wuxing, with the five elements Fire, Water, Wood, Metal, and Earth. Clearly, each of these crucial elements is of utmost importance to everything that exists.

Earth includes a variety of rocks and minerals, organic matter, sand, all kinds of organisms, water, and gases. But those are just words, name tags, place holders. More appropriately, it’s called “the stuff of life” because it is full of life (when it’s healthy), plus it keeps living beings alife. Yes, even fish and other critters that live in rivers or oceans depend on soil – rain washes nutrients into the water, helping its occupants to grow. Humans should treat the soil kindly, with gratitude, something that rarely happens.

That’s why I was so excited when I learned about an exhibition at Somerset House in Central London. Called SOIL – The World At Our Feet, it combines the work of artists, scientists, musicians, gardeners, and writers from all over the world. Visitors will be immersed in sounds and visuals, they can participate in events and activities, watch films, explore the nature of soil, and – DRUMROLL! – eat a meal at the (mostly) vegan Café.

I was intrigued by the message and the focus of this exhibition. Literally and metaphorically, the tangled web or network of roots and mycorrhizal fungi, with their tubular cells called mycelium has fascinated me deeply and is the perfect symbolization of Celebrating Connectedness. I started out with a focus on plant-based living, but when I learned more about the understory – I was hooked.

I decided to explore some of the artists, scientists, and organizations involved in this exhibition, and I want to share what I discovered, hoping that you will find it as exciting as I do.

For example, listen to the bioelectrical sounds that Turkey-tail Mushrooms and Fairies’ Bonnets emit, recorded by ecologist, botanist and composer Michael Allen Z Prime from Cork, Ireland. He uses the sounds with his compositions of “Bioelectrical Music”.

The use of bioactivity translators to amplify the electrical activity of plants and fungi has been central to much of Prime’s work. Through the medium of sound, listeners are able to enter and interact with the transient world of plant reactions.1 He must have been inspired by Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, who spent the first decades of the 20th century investigating the science now known as plant neurophysiology. He constructed micro-electrodes capable of taking precise electrical measurements from single cells, decades before any such equipment was constructed for investigating animal cells. His experiments showed that electrical impulses (the bioelectrical field) are responsible for the control of many physiological impulses in plants, including growth, ascent of sap, respiration, photosynthesis, motor activity, and response to the environment.

With his work, Prime strives for interspecies collaboration, maybe even communication.

When one considers that “a cup of healthy soil contains around 200 billion bacteria, 20 million protozoa, 100,000 nematodes, 100,000 meters of fungi and probably one earthworm”2 this cup of soil literally springs to life before one’s eyes. Just think of all this activity: moving, reproducing, shape-shifting, eating, eliminating, being born, growing old – everywhere right underneath our feet. But – “They paved paradise and put up a parking lot” – Joni Mitchell, 1970.

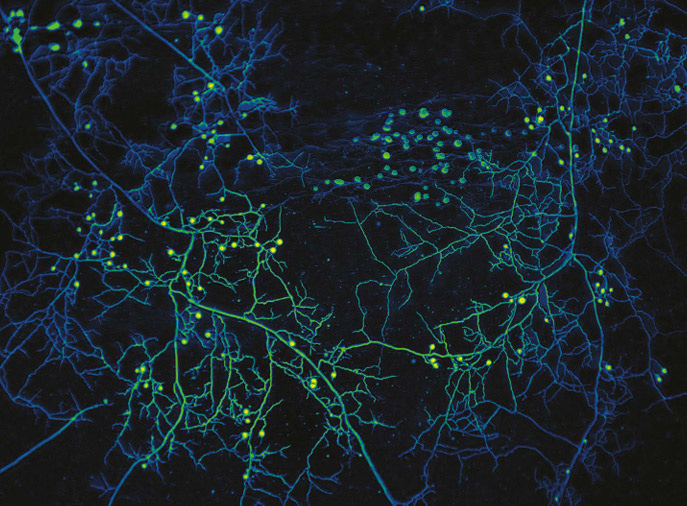

Wherever mycorrhizal fungi and their amazing symbiosis with plants are the focus of attention, one can be sure that biologist and mycologist Merlin Sheldrake is involved. He is the narrator for Marshmallow Laser Feast’s “Poetics of Soil” video installation, an artistic representation of something that’s normally invisible because it takes place underground. It’s based on a recent peer-reviewed article published in Nature titled A traveling-wave strategy for plant-fungal trade, the result of the collaboration of scientists from various European and U.S. universities, one of them Sheldrake. The research project established that fungi have built efficient networks which allows them to trade nutrients with plant roots. Looking similar to a network of streets, highways, and multi-lane freeways, the fungi networks are self-regulating and constantly changing, in order to provide the best nutrient trade.

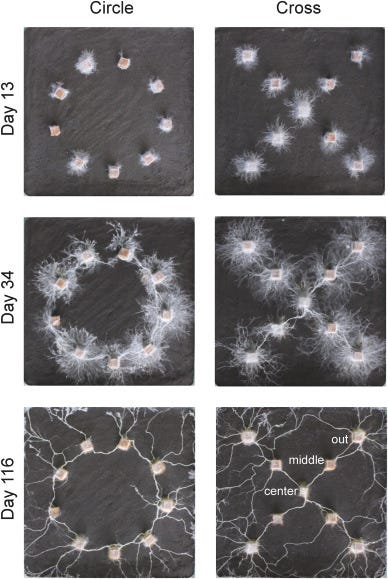

In 2024 Japanese researchers had established that fungal mycelia have memories, can make decisions and solve problems. They based their study on the question: “Can organisms without a brain still show signs of intelligence?” Based on the mycelial networks that developed around the two test shapes of wooden blocks – a circle and a cross – scientists concluded that the network could communicate information across distances and change direction of growth depending on what would be most beneficial for the whole system. But these changes are not centrally controlled, there’s no one “authority” which tells the mycelia how and where to grow; instead, they “emerge from the collective behaviors of numerous hyphal tips, each sensing environmental conditions, interacting, and networking with one another”.3

The paper A travelling-wave strategy for plant–fungal trade mentioned above, which inspired one of the installations of the SOIL exhibition, added another piece of information to the current knowledge of these fungal networks. Self-regulating traveling waves have built supply-chains that are both expansive and efficient. Traffic in the hyphae (that’s what the long, filamentous branches which form the mycelium are called) goes both ways, like two-way highways. Although two-way traffic is more efficient than one-way traffic, it is also more easily congested. When that happens, the hyphae can widen – similar to adding a few lanes to a busy highway. If there’s an obstacle in their path, they quickly find new ways around it. And somehow, whatever is happening in one part of the vast network causes instant adjustments in other parts.

How is this even possible? There’s no brain, no mouth, no central nervous system, and yet, they do a sophisticated job that’s absolutely essential for life on our planet. Some 800 million years ago ( a vague number because there are few fossilized fungi) the symbiotic relationship between plant roots and mycelia made it possible for plants to live on land rather than in water, and created the soil and atmosphere that allowed the evolution of life in all its current shapes and forms. Scientists know relatively little about this vast kingdom. Actually, before 2007 the Kingdom Fungi didn’t exist because they were considered to be plants. As strange as it sounds, a mushroom is closer related to animals than to plants – but they do have their own classification now.

The way scientists, artists, writers, gardeners, and musicians connect their work to create the SOIL exhibition reminds me of the mycelium network and of all the intertwined networks that form the biosphere. Actually, each human is an ecosystem which hosts billions of microorganisms, and they all collaborate quite well mostly. Which one is “me”?

For my relatively new subscribers, below are two links to pieces about being connected:

https://jessicarath.substack.com/p/so-what-about-this-connectedness

Really fascinating, Jessica. Thanks. I remember seeing a video/movie about mycelium and it was incredible.