After the long drive through Turkey and Iran, Kabul was a veritable refuge. Situated in a valley of the Hindu Kush mountain range west of the Himalayas, 5,873 feet above sea level, its semi-arid climate meant that it was sunny and dry when we arrived in November. Compared to cold Germany, the temperature was delightful, the sun was shining, and there was no rain. We found a cheap hotel with a large open courtyard where we could park our bus (there were many of them, and just about every hotel in Kabul was cheap compared to European pricing), and we allowed ourselves a few days of rest and exploration.

My experience of being in public had become increasingly unpleasant as we drove through Turkey and Iran. Although I was always flanked by two young men when we walked around, it would happen that somebody would pinch my butt when we strolled through a market, or somebody would “accidentally” brush my thigh. I preferred to stay in the van whenever possible; it was simply obnoxious. When we reached the eastern parts of Iran, my perception of most males being lewd and smarmy changed – they seemed less repressed and more independent.

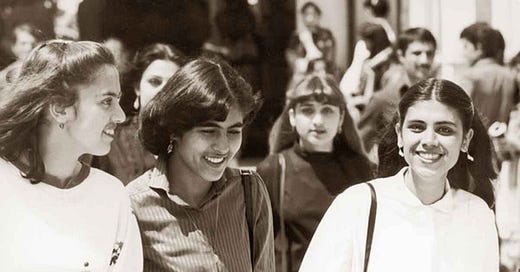

Once we reached Afghanistan, men weren’t as revolting any more. I learned to love the people. Maybe Kabul’s atmosphere wasn’t typical for the rest of the country, but we met a modern, emancipated city where tradition and progress existed happily side by side. There were many foreigners – not only tourists and hippies, but also shop owners, restaurateurs, and other entrepreneurs from France, England, Germany and other countries who had chosen Kabul as their new home. We’d meet little girls on their way to school – easily recognizable by their neat uniforms: short, pleated skirts, blazers on top of white shirts. When we visited the university, we saw many young women on their way to taking classes. Burqas – or chadarees, as they’re called in Afghanistan – were rare enough to pique my curiosity: why would anybody wear them?

I know now that we experienced the last few moments of what is called “The Golden Age” – roughly the time between the mid-1930s and 1973. The last king of Afghanistan, Zahir Shah, spent some time in France as part of his education; that’s where he probably got his pro-Western, pro-democratic ideas. He became king in 1933, a few hours after his father had been assassinated. Because he was only 29 at the time, his uncles were the de-facto rulers, but he slowly asserted his own powers. In 1964 he initiated reforms which provided for a parliament, elections and a free press. He introduced a constitution which turned Afghanistan into a modern democratic state. People enjoyed free elections and social reforms. The status of women improved tremendously. Zahir Shah’s wife, Queen Humaira Begum, had already been a trail blazer when in 1959 she appeared in public without a veil.

Her example was soon followed by the wives and daughters of government officials, and by the majority of women when I visited Kabul in 1970 and 1971, or so it looked to me.

In 1973 the king abdicated after one of his cousins, Daoud Khan, staged a coup d'état and established a republican government (Zahir Shah and his wife lived in exile in Rome for twenty-nine years). In 1978 Daoud Khan and most of his family were assassinated by rebel Afghan communists which led to the invasion by Soviet Union forces in 1979.

Since then, violence, wars and oppressive regimes have destroyed much of the city. On my way from India back to Europe I spent several weeks in Kabul, just about a year after my first stay. The people were friendly and kind, the men didn’t pester me, the city was open, tolerant, and quite cosmopolitan. It’s deeply painful to know that a place that one cherished has been destroyed.

And guess who stated they’re “open for a new chapter of relations”, right after Trump won the election? Yes, the Taliban. Their foreign ministry spokesman Abdul Qahar Balkhi tweeted:

The Doha Agreement signed between the Islamic Emirate and America under President Trump’s administration lead to the end of the twenty-year occupation…Furthermore, it is expected that Mr. Trump will assume a constructive role in ending the current conflicts in the region & globally, particularly the ongoing brutality & aggression in Gaza & Lebanon. 1

That deal cut out the Afghan government and committed the U.S. to leave Afghanistan by May 2021, closing five military bases and ending economic sanctions on the Taliban. This paved the way for the U.S. evacuation of the country in August 2021 and the return of the Taliban to power. The Taliban prohibits girls’ education past the sixth grade and recently banned the sound of women’s voices outside their homes. 2

After this short digression I’ll return to November of 1970 in Kabul. I think we spent about one week there, reluctant to leave the comfort that was offered there. We knew that the next stretch of the journey would be tough. But India beckoned.

To reach Pakistan, we had to cross the Khyber Pass – an historically important part of the southern route of the Silk Road connecting Central and South Asia, and always an adventure to pass. At some points, the road is less than three-and-a-half yards wide!

When you consider that the road is used mainly by trucks which frequently break down and cause huge traffic jams, you’ll understand why the trip is always full of surprises. Add the fact that on leaving Afghanistan one has to drive on the wrong – make that the left – side of the road! From one moment to the next. Actually, crossing the Khyber Pass wasn’t so bad as far that is concerned; going straight was relatively easy. Making turns – especially turning left – one could easily end up on the right side of the road, which was rather dangerous.

The distance from Kabul to the Indian border is roughly 525 miles. I remember that we drove through Islamabad, a planned city which became Pakistan’s capital in 1966 and was still in construction stages and nothing much to look at when we visited. A flat tire is another memory; several friendly men came to help almost immediately, every one of them carrying a rifle and ammunition, which was a tad disconcerting.

We reached the Pakistan-India border on the day Ramadan ended, December 1, 1970. The border agents were in a festive mood and served us tea and cookies; they admired my long, red hair and blue eyes, and were altogether pleasant and charming. And so we finally reached India! The Indian bordertown was Ferozepur in the state of Punjab, which had a large Muslim population in the 1970s, and we were treated to tea and cookies once again, a lovely welcome!

I spent over a year traveling through India, Kashmir, and Nepal; sold the car, and said good-bye to the boyfriend. Maybe this will be a new section of this travel journal.

please write more! i love overland-to-india stories and that route would be the one thing i’d bring back from the dead if i could!

A very exciting story all around. From the time you left home, how long was it to the Indian border?