When I started this Substack, I wanted to promote a vegan lifestyle. The suffering of commercially raised animals who end up in supermarkets, neatly wrapped in plastic so there’s no blood and it’s easy to overlook that they were living, feeling beings, had to be emphasized. It was most dear to my heart.

Over time, my outlook broadened. I learned that being vegan involves much more than a diet, and that the industry of animal agriculture is a huge contributor to the greenhouse gases that destroy the climate and the planet. Multi-national corporations have swallowed up smaller farms, so that by 2024 99 percent of all farmed animals – cows, chickens, pigs, fish etc – live in factory farms or CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations). Less than 25 percent of farms in the U.S. are small to medium-sized and owned independently. The industry has an immensely powerful lobby with seemingly endless financial resources. In 2024 for example they spent close to $180 million, allowing them to whitewash and suppress any mention of the devastating environmental effects of the agribusiness, while badmouthing meat-alternatives.

So, why wouldn’t most people stop eating meat, when there’s such convincing evidence that it’s bad for the planet, the animals, and their health (there is plenty of proof for that as well)? For a number of reasons, probably first and foremost the fact that they’re used to it, and it tastes good. Then there's the cognitive dissonance that many people experience when it comes to eating animals. “Why do I feed my cat but eat a chicken?”, or “Factory farms don’t treat animals well, but I like my hamburger”. Psychologists have a term for it: Meat paradox.

There are various strategies that help to avoid internal conflict while enjoying barbecued ribs, but the one, fundamental, reason why it’s so easy to sweep all discomfort under the rug has to do with the way we humans perceive ourselves and the world around us. It is based on a model of perception which is outdated, doesn’t work any more, and has become actively destructive. It has to do with who “I” am.

Western culture and science is based on a hierarchical model of “nature” which posits the human being at the very top of evolution, as the crown of creation of Christianity and other Abrahamic religions. Being at the top means one is the strongest and in charge. All other creatures are inferior and can be exploited, used, abused. It is a model which has led to devastating results: white supremacism, patriarchy, and authoritarian dictators.

Compared to other beings, we humans have a strongly developed ego-awareness. “I am …”: fill in the blanks, a woman, a grandfather, a Donaudampfschiffahrtsgesellschaftskapitän (sorry, I’m being silly, but I had to include this; in German, one can string multiple words together; it means “Danube steamship company captain”; I could have used “a butcher, a baker, a candlestick maker” instead.) I am always at the center of everything I can see and perceive. All other beings, whether human or not, seem separate from me, some more, some less on the periphery, depending on their importance to me.

Maybe from an evolutionary point of view, this strong ego-consciousness was necessary. It gave rise to famous empires – which eventually collapsed. And it led to the colonization of many parts of the world, causing unfathomable suffering which still reverberates. Unheeded early-warning signs.

Today, the hierarchically structured, from-the-top-down worldview is driving the Earth to a full-blown catastrophe, and that’s putting it mildly. If you think I’m exaggerating, please look at just two of The Guardian’s articles from June 5: the first one documents the enormous decline of insects over the span of 25 years, in Area de Conservación Guanacaste, a protected region in Central America. The other article claims that almost 40% of the world's glaciers is already doomed due to climate crisis.

If we humans want to survive on Earth (I believe she’ll do just fine without us, but…) a radical shift in our thinking, feeling, and perception is absolutely essential: instead of the vertical, from-the-top-down alignment, we have to adopt a horizontal worldview – although this sounds too one-dimensional. The opposite of a vertically aligned, hierarchical worldview looks more like a multi-dimentional net, where everything is connected but no single node is permanently in the center, because there is constant change. It means making a conscious effort to refrain from anthropomorphizing all creatures around us, and I interpret this word in the almost completely opposite way from its common meaning. Look at this sentence from an article about anthropomorphism from Psychology Today:

“Perceiving the presence of human qualities in other entities can be misleading when such qualities are absent.”

It posits that qualities such as love and characteristics like intelligence are exclusively human. To deny non-human animals the capacity for love seems so arrogant, and yet, it is a common attitude among some scientists, as I have personally experienced. A being that’s unable to love you – maybe it doesn’t deserve to be loved by you, to be treated with kindness, with respect. Maybe that attitude is a prerequisite for vivisection and animal experiments, because it's not so easy to hurt a being that you love.

The current dominant worldview which puts us humans at the top and is entirely anthropocentric becomes increasingly untenable. Which means it has to change – we have to change – unless you belong to the ultra-rich, in which case you can buy a luxury underground shelter: a Survival Condo, or a super-luxury Bunker, with a decontamination room, water & gas tight doors, and a gun room/range. I’m not kidding, follow the links.

Luckily, a number of individuals and groups are promoting and acting on such a change. I thought I’d compile a list of some of them, for those of you who share my urgency in the face of the rate of species extinction, of the suffering of the many billions of animals killed for food each year in the U.S., of the looming threat of wildfires and extreme temperatures.

They are researchers who focus on connectedness, those who study network-forming fungi and their communication with the roots of plants. First, there are the tree women: Suzanne Simard, Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia, who discovered the way trees communicate with each other by utilizing mycorrhizal fungi.

On a similar track, the Irish botanist and biochemist Diana Beresford-Kroeger discovered the importance of mother trees forming centers at different parts of the forest and, like Simard, scientifically verified that trees exchange vital information about nutrients and water resources. The mycelial networks created by fungi make this possible.

“All things are connected on planet Earth, from the burning eye of the volcano and the brilliant colours of a butterfly’s wing, to the chlorophyll of plants and life within the seas. In recent years the tapestry of life has been damaged.”1

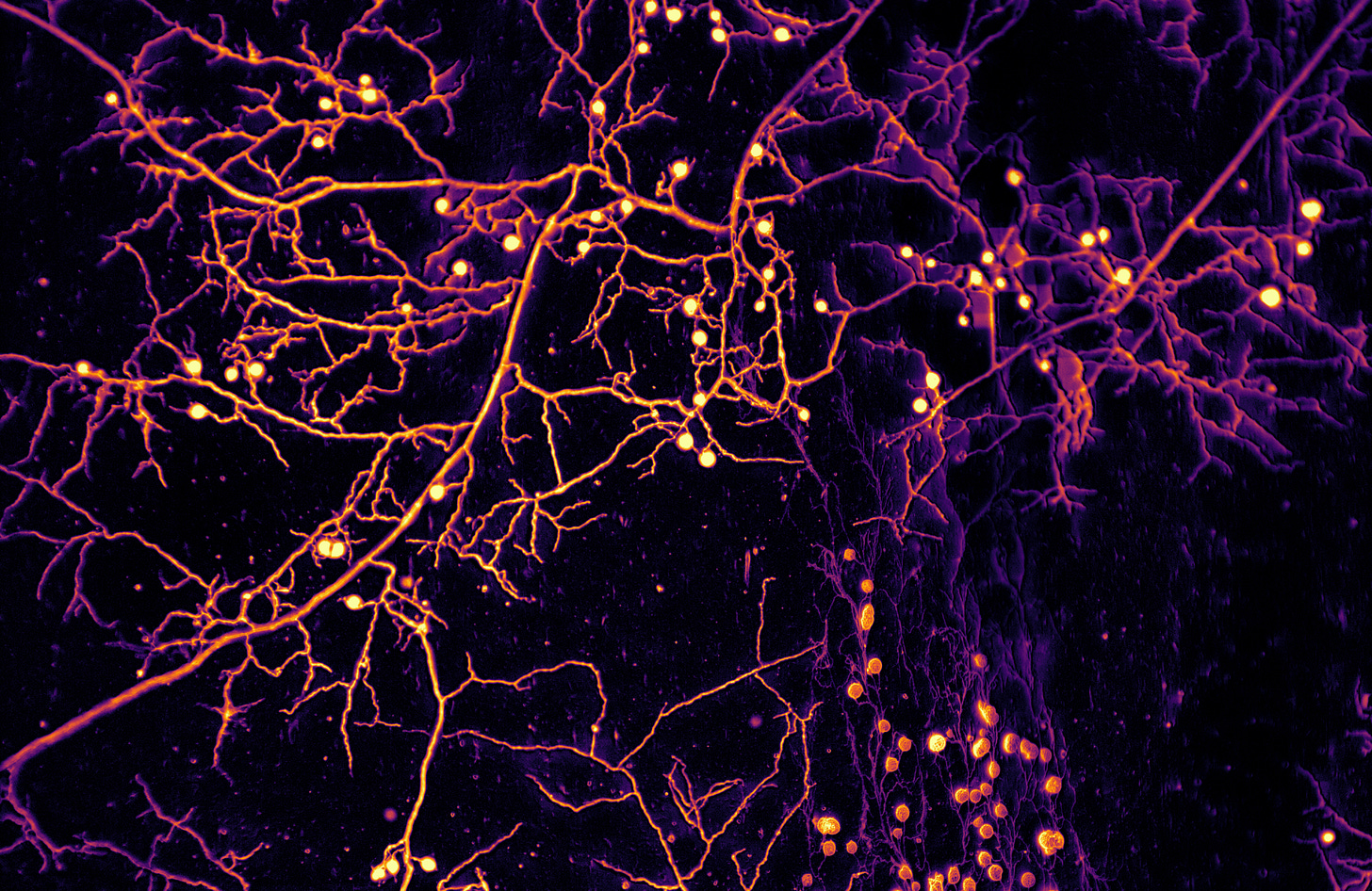

And then there are the fungi-people. Mycorrhizal fungi and their network-forming abilities (they create something like trade-routes, similar to underground subway systems, by which they exchange resources and information. Without a brain!) have inspired a new field of research. These scientists are fascinated by this different way of processing information and decisionmaking: how do fungi exchange resources? How does this underground infrastructure grow?

Merlin Sheldrake (author of Entangled Life) is probably the best-known mycologist, but there are others, and they all are intertwined and working together, just like their research subject. I’ll mention just a few: there is British mycologist and Harvard University associate Giuliana Furci, founder of the Fungi Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and recognition of fungi. Note that they were considered to belong to the plant kingdom, and only in the middle of the Twentieth Century, with the advent of molecular analysis, were they recognized as a separate kingdom – neither plant nor animal, but something in–between. It is assumed that there are some 2.2 million to 3.8 million species of fungi, but only about 148,000 have been recognized! That’s why organizations such as the Fungi Foundation are important: they need to be mapped and protected. SPUN (Society for the Protection of Underground Networks) is another such organization. Make sure to visit their website, they have some stunning visuals!

And just when I’m almost done with my piece I receive an email from Emergence Magazine, a publication that shares “stories that explore the timeless connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality.” It links an essay by writer and artist

, Supracellular – A Meditation. She says everything I tried to communicate here – but so much more eloquently!“Many days I have sat at the river and imagined I am water. Fire. Air. Elemental. Matter flowing through other matter. A hummingbird. A sturgeon. The wet-eyed opossum under the barberry bush. The barberry bush… The exercise necessarily fails. But the empathy muscle it strengthens is crucial.”

YES. Let’s strengthen our empathy muscles.

Excellent post. Love the SPUN site, and ordered Sheldrake's book. Our understanding of the planet continues to evolve, hopefully in time to end or reverse our damage.