Where’s The Spark,

Part II

To continue from September 6: The Nazi-time and World War II dampened the creative output of many avant-garde artists. Those who were identified by the Nazis as degenerates and were included in the Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich and later in Berlin and other German cities went into exile; certainly so if they were Jews or known communists. Others who chose to stay in Germany were forbidden to paint, buy the materials they needed, were not allowed to teach at universities, and had to endure occasional raids by the Gestapo.

French artists, writers and intellectuals had to flee as well, after the Germans invaded France in 1940 and forced an armistice which resulted in the installation of the Vichy Regime under Marshal Philippe Pétain. A reactionary authoritarian, he collaborated with Hitler and installed laws that endangered the lives of Jews, communists, and soon anybody who joined the growing resistance. Since many Germans had escaped to France at the beginning of the Nazi time, there was a huge number of refugees trying to escape to the U.S.A. Once immigration policies became so restrictive that visas for the United States became all but impossible to get, people had to be smuggled out of France, to Spain and Portugal. Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee helped around 2,500 Jews, Nazi-dissidents, artists, composers, writers, and scientists to avoid the French concentration camps and to escape.1

After the war people had to pick up the pieces of their disrupted lives, no matter where in Europe. Even during the war there were extreme food shortages, such as the Dutch Famine of 1944-45. After 1945 all nutrients were strictly rationed. In occupied Germany, for example, daily rations for an adult provided only about 1,000 calories. In Brittain, rationing and food shortages were worse than during the war and continued in some form until 1954. In France, access to food was regulated by the government until 1949. There were millions of displaced civilians, seeking new homes, and millions of bombed-out houses that had to be rebuilt. No wonder there were hardly any new ….isms.

The next major “spark”, in Europe at least, was Existentialism. Although some of the works that defined it were written earlier, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus became fashionable in the early Sixties, at least in Europe among young students and intellectuals. Paris was the center of attraction for young people intrigued by a philosophy that explored concepts such as freedom, meaning and value of life, or the possible absurdity of existence. Existentialism’s concepts spilled over into literature, film, and theater, which greatly enhanced its popularity.

I remember the first time I visited Paris; I was sixteen or seventeen, and it was a one-week trip organized by my school. Strolling around the Rive Gauche, the left bank of the River Seine, was a dream come true: it is the site of the Quartier Latin, the Sorbonne University, and the district of Montmartre, made famous by painters such as Renoir, Picasso, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec. In the 1920s and 30s many artists migrated to Montparnasse because it was cheaper, and most artists and writers were penniless. The cafés and bars where expatriates from the United States – Henry Miller, Ernest Hemingway, Alec Baldwin, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and many others – had gathered, and where the existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus had written their seminal works, survive to this day. To sip strong, black French espresso in those spots, dressed in black like a true existentialist, smoking Gauloises was a fabulous adventure for this teenager.

I also noticed that the French kids I met were proud of France. Which made me aware, for the first time, that I was not proud of being German. After the Nazi time that was simply impossible. It remains a fact that I’m grateful for: I’m forever allergic to nationalism. Why should I be proud of something that I had no control over?

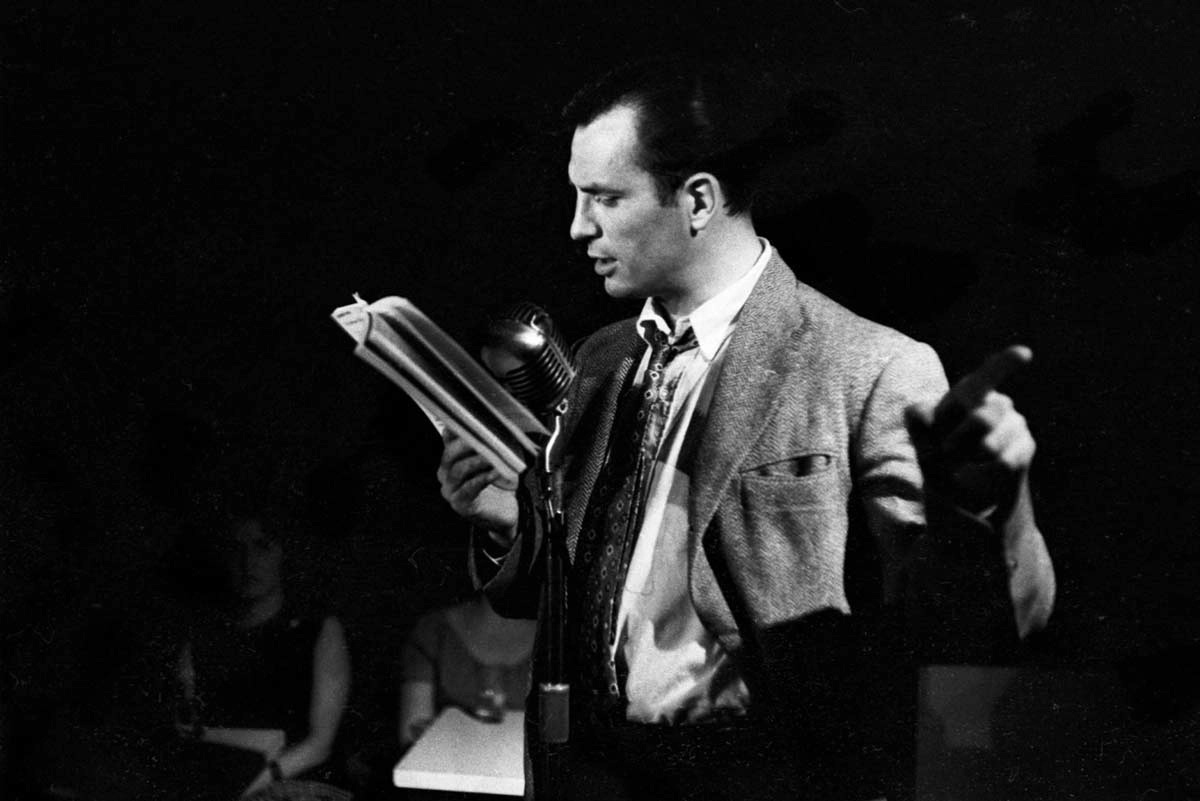

Another “sparkly” period, the Beat Generation, was a literary movement that rebelled against traditional norms and explored the human condition after World War II. Their writers and poets, such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Neal Cassady, and William S. Burroughs, and the subculture that formed around them (the Beatniks) were less directly influential in Europe, although Charlie Parker and Miles Davis were musicians I preferred to the “Beatlemania” of 1964. I felt I was more sophisticated than swooning teenyboppers. The names of Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg eventually merged into the counterculture of the late Sixties, when I discovered their work.

Which brings me to the spark that literally changed my life and made me the person I am today: the late Sixties. My father was a doctor and my family belonged to the conservative upper middle class, and from my first day of school I knew I had to go to university. “Knew” is somewhat incorrect, it wasn’t a conscious decision and I had no say in the matter. In the German school system after four years of elementary school one enters the Gymnasium, a secondary school that prepares its students for university. To become a firefighter, a hairdresser, or a photographer – that simply wasn’t a choice. After I finished grade school in 1965 (at that time, it took thirteen years), I enrolled at the University of Munich, as far away from my home town as possible.

In June of 1967 I joined my first demonstration, to protest the shooting of Benno Ohnesorg who was killed by a policeman during a rally against a state visit by the Shah of Persia. Besides becoming politically active, I also started smoking pot, taking LSD, ditched the notion that sex was allowed only when you were married, and tossed out anything else conventional: clothes, hairstyle, worldview, you name it. Eventually, at the end of 1970, I drove overland to India, see the “Travel Journal” tab in the menu on top.

Where is our next spark? I’ll keep exploring.

An immensely fascinating story that also involved the American Vice Consul in Marseilles, Hiram Bingham. Here is Varian Fry’s chronicle: Surrender On Demand.

Very exciting to read. I think of my parents arriving in Berlin in 1952, he was 26 and she was 22. What a job at such a time and place.

I'm envious of your travels. Lovely 😍