Did you know that the approximately 300,000 species of flowering plants fall into two large categories, the monocotyledons and the dicotyledons? The cotyledon is the first thing that emerges from the top of a seed. In the case of the monocotyledons (or monocots, as they’re commonly called) only ONE leaf emerges from the seed, while with the dicotyledons (or dicots) TWO leaves appear. These are actually pseudo-leaves and look more or less the same, no matter whether it’s a sunflower or a tomato. Only the next set of leaves is typical for its particular plant. Then the leaves of a sunflower are easily distinguishable from the leaves of a tomato plant.

There are other, profound differences between the two groups. First, some general characteristics: Examples of monocots are grasses, including those that produce the grains that are staples of our daily meals such as wheat, rice, corn, barley, rye, oats, etc., but also palm trees, sugar cane, and bamboos. Ornamental flowers such as orchids, tulips, daffodils, and lilies are monocots.

Dicots, with 200,000 species the larger group of flowering plants, include roses, sunflowers, poppies, and daisies as examples for ornamental flowers; fruit trees such as apple or peach trees and flowering vines such as grapes; all sorts of beans and peas; and most berries: raspberries, blackberries, strawberries, etc.

So, what are some of the differences between monocots and dicots? Can the adult plants be as easily distinguished as the first leaf/leaves?

Indeed, every part of a plant from the two groups is fundamentally different. Let’s start with the root system. Dicots have a taproot, like the carrot, for example. The main root grows downward and is long and deep, with smaller, lateral roots branching off. Monocots, on the other hand, have a fibrous, net-like root system that spreads horizontally. Some monocots grow from rhizomes, a horizontally growing stem-like tuber or bulb which sends out new shoots. Irises and lilies propagate that way.

Leaves and stems have distinct differences as well. The veins of dicot plants are net-like and branching, whereas monocot leaves have parallel veins — think of grasses or green onions. Monocots have stems that typically are hollow and flexible, while dicots’ stems are often woody.

The flowers of monocots often have six (two times three) petals, such as tulips, daffodils, irises or lilies. From an archetypal standpoint, flowers belonging to the dicot group have five petals – fruit tree blossoms, wild roses, hollyhocks, hibiscus, and zucchini blossoms, for example. Go ahead and cut an apple in half; you’ll discover a little five-pointed star.

When you have time, go and look around in your garden, or take a short walk around the block. Notice how many flowers and plants of the rose family and the lily family you can find.

Here in my garden in Massachusetts, daylilies are everywhere. Irises have finished blooming and display big seed pods. Hostas (also known as plantain lilies) like to grow in the shade under trees, where they spread like a (pretty) weed via rhizomes. As explained above, those are horizontal stems which grow underground, close below the soil level.

As far as the rose family is concerned, the hollyhock and the morning glory pictures were taken in my garden in New Mexico. Zucchini grow everywhere, and I have many beautiful blossoms here in MA. Notice the five-fold star in each of the samples below.

If you really want to know a flower or plant a little better, look at it carefully for a while, from all angles. Just notice what you can see – the color, the shape, the edges, the texture. Try not to interpret what is in front of you. Try not to name things – “This is a sepal, a stamen, a pistil” – and more than anything, try to keep personal feelings and associations out of your observation. When you look at a flower that’s partly wilted, refrain from saying that it looks sad; instead, observe how it’s curled up or has changed its color.

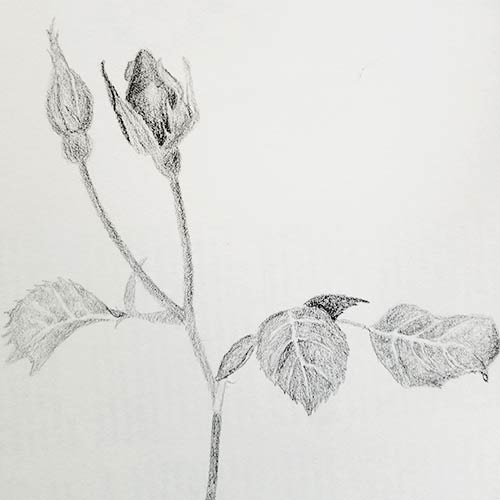

Next, take a drawing pad and a soft pencil and draw what you see. You don’t have to be an artist; using a soft pencil allows you to gently correct your lines. Actually, if possible, don’t start with lines – there are no pencil lines in the world around you, only edges created by different surfaces, and light and darkness. With the flat side of a soft pencil you can move in from the outside, so to speak, as in the iris drawing on the right. The edge between the flower petal and the background becomes visible where you stop the pencil.

Observing a plant or flower in this manner is based on the scientific methodology of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. If this interests you, I wrote about his way of examining the world in October of 2022. When your eyes become like fingers, as it were, exploring a flower in an active, attentive manner, you begin to experience WITH the flower – an entirely different process from reading ABOUT it.

And now we take a quick look at the symbolic meaning of roses and lilies, and examine whether there are any correlations with the way the actual plants grow.

Red roses have been associated with love and passion ever since ancient Greek mythology when they were a symbol of the goddess Aphrodite. Red is the color of blood, and maybe the fact that a rose’s thorns can draw blood helped to connect the flower to earthly love which often is painful as well as all-consuming. The root grows deep into the earth, another characteristic that points to the rose’s worldly, incarnated nature.

The lily, on the other hand, is characterized by more “otherworldly” symbolism: death and rebirth, innocence and purity. In medieval paintings its pure white petals are often used to represent Mary’s chastity and virtue. When it is associated with death and funerals, it points to spiritual rebirth and new beginnings. Again, the root system supports these ideas – as we saw, the lily’s roots are close to the surface and don’t penetrate deeply into the earth. But even a small part of a rhizome can produce a new shoot, a new flower.

When I lived in Berkeley/California (roughly from 1978 - 2000) I took part in a rather unconventional training. Maria de Zwaan, an Anthroposophic Arts Therapist from Zeist, Holland, gave an introductory course about her way of practicing art as a therapeutic tool. Soon after, twelve of us participants committed to exploring this more deeply. Under Maria’s guidance, we met once a month for an entire weekend (Friday evening, all day Saturday and Sunday) when we studied selected texts, practiced countless artistic exercises which involved watercolor painting, various drawing techniques, and clay modeling, and took turns giving presentations. This went on for five years during which Maria came every summer to teach us for several weeks. The training culminated with a final two weeks of learning in Chartres/France, when we stayed in an old monastery close by the cathedral.

It was an unforgettable experience. Some of us who finished the training went on to give workshops in the San Francisco/Bay area and other parts of the U.S. We called it “Nurturing Arts”. I was never really happy with the name; I wanted to help people to become more alert, more present – for me, the training resulted in being more awake to everything around me. Which includes the firm conviction that I’m part of everything around me, and vice versa. However, “Wakeup Arts” sounds weird, and I could not come up with a better name. So, Nurturing Arts it is for the time being.

Fascinating Jessica, very holistic connectedness with art, science, prose, photography, history. Wonderful, in the true meaning of the word.

Very interesting, abundantly illustrated with beautiful photos. Now I understand much better the differences between monocots and dicots, thank you Jessica 🙂.

Beautiful photo as well of Chartres Cathedral, one of the most admirable and the best-preserved examples of Gothic art.