To say that opinions and viewpoints are currently extremely polarized seems almost trite, it is so obvious. How to reconcile the seeming craziness, how to make sense of the daily assault on what one believes to be good and true is almost impossible. It might be useful to take some steps back to try and get some wider perspective – to look at humanity’s collective psyche with a bird’s-eye view. Or better, with a time-lapse recording device: have there been changes over many centuries? Or is humanity simply repeating the same mistakes over and over again, against the backdrop of different costumes and technologies?

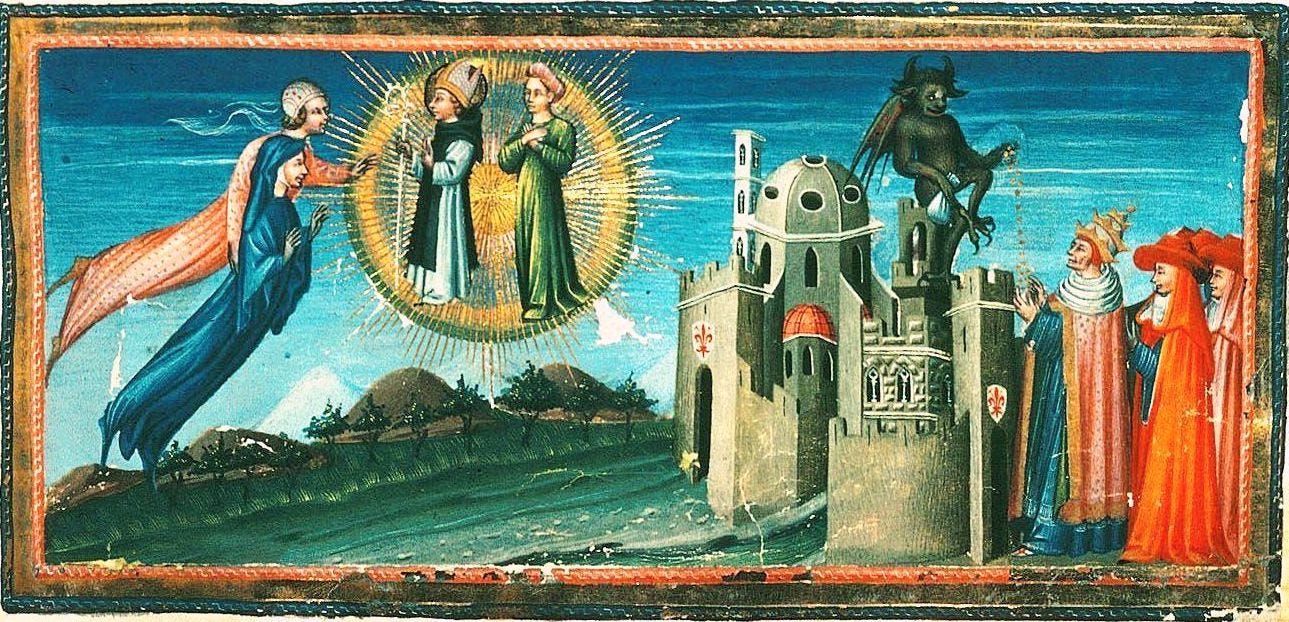

I decided to look at two iconic literary works, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, written between 1308 and about 1321, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, a tragic play in two parts which the poet and playwright worked on for most of his life, between 1772 and 1831. Both books feature a protagonist who is on a journey: Dante travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Faust’s journey takes him through life on Earth in Part I and through Heaven in Part II. Both have a mentor: Dante’s is the ancient Roman poet Virgil who guides him through Hell and Purgatory. Faust chooses Mephistopheles (“not loving light” is one possible meaning of this name) who is a servant of the Devil or Lucifer. And both have a beautiful Muse: Beatrice, representing divine love, takes over from Virgil to lead the pilgrim Dante through Paradise. In Part I, Gretchen is Faust’s object of romantic love and desire, and in Part II becomes one of the manifestations of Goethe’s Eternal Feminine.

However, what both men were seeking was fundamentally different, it seems at first. The general worldview had changed tremendously.

Both Goethe's Faust and Dante's Divine Comedy are works of grand cosmological proportions, taking us through realms of heaven and hell populated by mythological, magical, historical, and angelic beings, evoking ancient and future times. The central theme, however -- the situation of the human being in relation to the cosmos -- is painted with strikingly different colors. Why would Dante call his epic work a comedy, whereas Goethe's dramatic poem is a tragedy? What constitutes Faust's character, and how does he differ from Dante the pilgrim? How could the two protagonists choose guides as diametrically opposite as Virgil and Mephisto?

Roughly 450 years had passed from the creation of the Divine Comedy until Goethe began his work on Faust, and human consciousness had undergone some significant transformations. Dante the pilgrim undertakes his ascent from the Inferno through the Purgatorio to the Paradiso with the firm conviction that the world and everything within it is created and upheld by divine powers, that the order and structure of the universe is a direct expression of God. In fact, this is more than conviction or belief; it is an unquestioned certainty which has not yet been undermined by doubt. Human beings could err and make mistakes, but they had a secure place in an ordered and meaningful world.

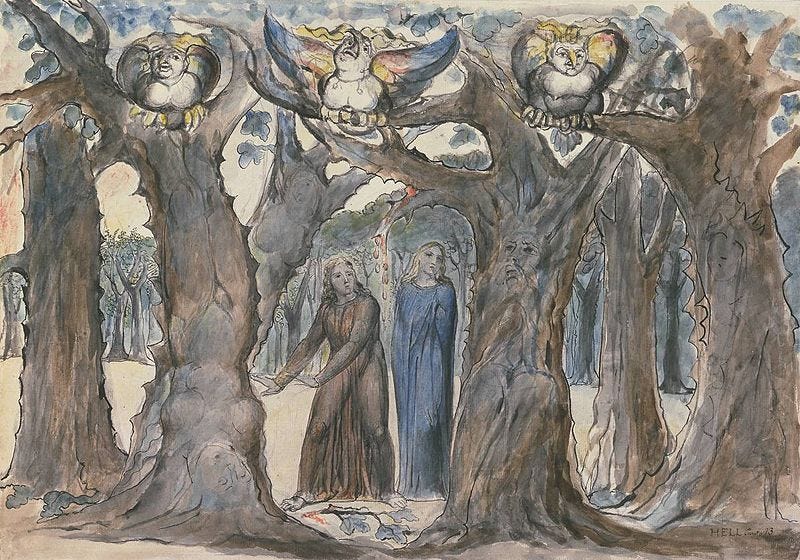

In The Banquet Dante describes this order which is based on the Ptolemaic geocentric cosmology. To its nine planetary spheres the Scholastics had added the Empyrean Heaven as the tenth sphere which was the most divine realm, the abode of the Supreme Deity. By assimilating Ptolemy's system to Christian iconography and symbolism, Dante wove together a vast panoply . This background provided a fixed and firm place for every creature and thing in the cosmic hierarchy. Positioned between Heaven and Hell, the human being was held securely, like a baby in the cradle.

From the cosmic perspective of such a world view, earthly tribulations ultimately dissolve as impermanent and transitory stages of the soul's journey back to a reunification with the Absolute. What seems tragic from a human perspective is embedded in the Divine Comedy, the all-encompassing Love of God. Although one rarely laughs when reading Dante's work, and the stark pictures of the Inferno are disconcerting and startling, the state of pure bliss and joy evoked in the Paradiso which is attainable with earnest striving, gives confidence in the basic goodness of creation, and is the direction of the gaze of human earthly existence.

And then the Renaissance with its interest in humanism and science came along. When a system becomes habitual and static, any change causes a disruption of the whole structure. Once the frozen conventions of the Middle Ages began to thaw, their stability simply melted away. By Goethe's time human consciousness had adopted a rational, scientific attitude, based on intellectual evaluation of observable facts, at the expense of imaginative vision. Copernicus and Kepler, Galileo and Newton were the heralds of a new world view which caused Dante's secure edifice to topple like a house of cards. The earth is not the center of the universe, but moves around the sun, like other planets. There is no limited and fixed number of spheres, in fact the universe is infinite. God and angelic hierarchies became more and more objects of philosophical debate, separate and removed from the physical world. Thus, Goethe's Faust finds himself in a fundamentally different situation from Dante, the pilgrim.

Goethe's dramatic poem starts in Heaven, and Faust's immortal soul is saved; hardly a tragic ending. However, it is the course of human earthly life which is the focus of the drama and which has indeed tragic proportions. Faust has often been called the archetypal modern individual, plagued by doubt, insecurity, and fear of an ultimately meaningless existence. But the story of Faust's passionate striving for knowledge and experience is not only serious; it includes comedy and satire, music and poetry, and is essentially universal in its scope.

After a short Dedication, Part I opens with the Prelude in the Theater, reminiscent of Shakespeare's "All the world's a stage". Together with the Prologue in Heaven, these prefaces to the play form a distancing frame of reference. The solemn Dedication by Goethe the poet, written almost 25 years after he first started to work on the subject, sets the tone for the play's fantastic character, evoking memories of old friends lost or dead, arising "out of the mist and murk" of the past. The more light-hearted Prelude in the Theater reminds us that a play is about to begin; right before our eyes and ears, the Director, the Poet, and the Jester discuss how we, the audience, should best be entertained. It is not an altogether flattering picture that reflects back to us -- the Poet calls us "motley throng", the Director's chief interest is our money, and the Jester knows what will satisfy us:

Colorful changing scenes and little sense, Much error, mixed with just a grain of truth - That's the best drink for such an audience, They'll be refreshed and edified.

But when the Director calls for action, he sums up what will be offered:

Thus on these narrow boards you'll seem To explore the entire creation's scheme - And with swift steps, yet wise and slow From heaven, through the world, right down to hell you'll go!

And this is the course of Part I: from the Prologue in Heaven to the state of Faust's soul after he has ruined Gretchen's life and has to leave her in prison, to be executed.

The important theme of polarity thus introduced, which weaves throughout both parts, is taken up again with the appearance of Mephisto in Heaven. After magnificent songs of the archangels praising God and the heavenly hosts, Mephisto's cynicism forms a sharp and jarring contrast. It is utterly impossible to imagine a hellish creature in Dante's Empyrean Heaven. Equally, the two opposing worldviews expressed by God and Mephisto would have been simply unthinkable at Dante's time. In Goethe's drama God is not so much a theologian or a Christian God as an exponent of Goethe's deep conviction of the positive workings of the universe, of the basic goodness of nature's eternal becoming. Likewise, Mephisto is less of an archetypal personification of the Devil but seems more like an exaggeration of human weaknesses and aberrations. In Goethe's cosmology where the realm of becoming is a constant weaving between polar forces, Mephisto is simply necessary to keep things running; he calls himself the "spirit of perpetual negation", but also knows that he is

Part of that Power which would Do evil constantly, and constantly does good.

He continuously seeks to destroy the light and the created world, but he knows his attempts are futile.

Faust will later call him a "strange son of chaos", archenemy of "the ever-stirring, wholesome energy of life", and advises him to find an occupation less doomed for failure.

The Divine Comedy begins in Hell, a frightening, gruesome place, and ends in Heaven -- the realm of ecstasy and eternal bliss. While today we may prefer to see these sites as inner states, stages of transformation of the individual, or even pure fantasy, one can rightfully assume that the reader at Dante's time believed in Heaven and Hell as fully real, actual locations. They were part of the one world view shared by every Christian -- that is, every individual in the Holy Roman Empire of the Middle Ages. This universality of the Christian faith had been shattered by the time of the Enlightenment, and at Goethe’s time there were different churches, sects, occult groups, free-thinkers, philosophers, not unlike today. Thus, the "Prologue in Heaven" does not reflect a universally accepted vision but Goethe's own. In the dialogue between God and Mephisto there is no mention of sin, evil, or eternal damnation, and with the beginning scene Goethe makes it quite clear that Faust's soul is in no danger to fall prey to the devil. "Man errs as long as he strives", declares God who knows his creations very well. The tragic proportions of human existence lie entirely in earthly life between birth and death.

While Dante the pilgrim displays an essentially humble disposition, striving to purify his soul from weaknesses and selfish passions, eager to learn what is good and noble, Faust has a more complex and conflicting character. He often reveals his hubris, his megalomaniacal sense of self importance which constantly alters with feelings of worthlessness. Seeking ultimate knowledge and understanding, longing to soar to new shores and to "the heaven's end", there is nothing moderate or modest about him. He desires extremes, not willing or able to enjoy any one mood for long.

The choice of Mephisto as a guide and companion also indicates the change in human consciousness since Dante's time. Where Virgil is a fatherly mentor whose sole aim is to educate his pupil towards a fuller realization of his affinity with the Beautiful, the True, and the Good, Mephisto plainly desires Faust's destruction.

Dante treats his guide with veneration and humility, but Faust more often than not expresses his contempt in Mephisto's company. It has been pointed out that Mephisto is Faust's Double or Shadow, personifying his repressed and unacceptable qualities. In this role, he is hardly fit to instill the fear of eternal damnation in Faust; he is more like a constant tormentor, forever spoiling the pleasures he promises.

Dante readily accepts earthly existence as a transitory stage on the way to eternal happiness and complete self-realization. Where else than on earth can the soul learn and grow? He accepts the guides who will lead him to the ultimate goal of the human being: to be at one with Divine Love and Infinite Goodness. This is a direct experience for Dante, a mystical experience of unity.

This vision, however, is not simply given to him. He attains to it only after his long and arduous journey through Hell and Purgatory. In order to go through the necessary transformation and purification willingly -- one has to engage a tremendous amount of will to pit against life-long habits -- the objective truth of the goal one strives for must be absolutely certain. One may reach the goal or one may fall short, but there is no question about its existence and reality.

By Goethe’s time faith had changed into belief which is impossible for someone like Faust who wants to know. Doubting Heaven means doubting Hell too, and all that is left to Faust, that concerns him, is the earthly realm. True to his earlier statement of not fearing hell or devil, or the loss of his soul (eternal life), he “dares the devil” by suggesting the famous wager:

If ever to the moment I shall say: Beautiful moment, do not pass away! Then you may forge your chains to bind me, Then I will put my life behind me, Then let them hear my death-knell toll. Then from your labors you’ll be free, The clock may stop, the clock-hands fall, And time come to an end for me!

This mirrors the bet Mephisto had proposed to God in Heaven, and it turns out that he is doing exactly what God wanted:

Man is too apt to sink into mere satisfaction, A total standstill is his constant wish: Therefore your company, busily devilish, Serves well to stimulate him into action.

With these words, God had given Mephisto permission to try and lead Faust astray, and when Faust now promises ceaseless striving, rejecting complacency and ease, both he and the devil are only following God’s plan. But if the wager is nothing more than a juxtaposition of empty earthly pleasures with empty threats of Hell, what is its meaning? Is it only an important dramatic device? I think in his innermost heart, Faust is yearning for a vision such as Dante’s, and his intention is to use Mephisto in order to reach this total experience, a moment of absolute wholeness. For Faust, as indeed for Goethe, the path towards such unity has nothing to do with transcendent or metaphysical realms but begins with earthly life itself.

If you want to reach the infinite,

Then explore every aspect of the finite,

Goethe wrote in one of his couplets.

The tragedy of human life then is not so much our ignorance of the secrets of the universe and the meaning of human existence; at least, it is not only this. Our confusion is caused by our own myopia and does not exist on God’s level. Dante’s vision has not been withdrawn from humanity, not even temporarily. It is simply hidden to the eyes of the intellect which can only separate and distinguish between parts. While an important and necessary achievement of the human mind, the intellect needs to be complemented by soul qualities which lead again to harmony and undivided unity.

In Part II, Goethe equals the Divine, or Universal Consciousness, with Love. It is not an attribute, a quality, but a fundamental condition, beyond the polarities of good and bad, right or wrong. God and Love are synonymous as the dynamic, moving power of the universe. Faust’s ceaseless striving during his earthly existence does not reach perfection, he does not turn into a faultless, ideal human being. Rather, his striving is itself a form of love, less perfect and pure than its absolute manifestation, but complementary to it. The dynamic tension in Faust’s soul leads to ‘enhancement’ (Steigerung), a process Goethe also observed and described in his studies of plant-metamorphosis.

The last scene of Part II is highly reminiscent of the final Cantos of the Paradiso, and Gretchen as Faust’s guide through heavenly realms plays a similar role as Beatrice. However, it is a person of flesh and blood who carries the action of Part I. While we can assume that the Beatrice who guided him through the Paradiso was not any less real for Dante than her (former) living counterpart, Faust’s passion and indeed love is only ignited and consumed by a real, alive person. Again, the focus is the realm of the earthly, sense-perceptible world. The vision of Dante’s Imaginations has dimmed and faded by Goethe’s time when humanity had turned its gaze fully toward the phenomena.

Goethe describes realities of soul and spirit which are hidden to a superficial, materialistic outlook. His worldview points to an as yet largely unrealized step in the evolution of consciousness: instead of only considering distinctly separate parts, his view emphasizes the connection to the whole, the underlying unity of the cosmos.

It could be that human consciousness is at the threshold of a similarly fundamental shift as the one which separates the Middle Ages from the Enlightenment. A shift that focuses on the way we are connected with and dependent on other beings big and small, that we’re not discrete units like Lego-blocks but intricately woven into every facet of life. The evil that seems to surround us is petty, ugly, and divisive. History shows that it doesn’t prevail.

damn girl you getting deep / guess i'll have to go read it now

really good post / i knew very little about either literary work or how it affected western culture / it all comes into focus now / humans will continue exploring and devising explanations for what they discover in their indefatigable effort to understand everything until one fine day when we realize we just need to understand ourselves / that's my comment