Honey Bees Are In Peril

And commercial beekeepers are freaking out.

Who knows why we feel more drawn to some creatures than to others. I dearly love the two cats I’m living with currently, but in general I’m more of a dog person. And I have a strong affinity for bees, not just an intellectual appreciation for the way they live and work together, but deep feelings of endearment and fondness. That’s why it hurts me when I find out that they’re being mistreated.

According to their website, Project Apis m. is a 501(c)5 non profit founded to support the best science to advance the beekeeping community. They conducted a survey and found out that commercial beekeepers lost about 62% of their colonies on average in early 2025. It’s the “biggest loss of honeybee colonies in US history”, according to Scott McArt, assistant professor of pollinator health in the Department of Entomology at Cornell University. This alarming colony loss mainly affects the profitability of the beekeeping industry. While they do mention that the food system that humans rely on is dependent on bees as pollinators, their concern about the bees’ health seems mainly utilitarian. They are a financial investment and some people experience pain because of all the money they lost, but no word about the millions of poor creatures who lost their lives.

Last year I interviewed a beekeeper in Abiquiú, New Mexico, somebody who found a wild swarm on his property, decided to offer them a home, and eventually had about 18 hives. He sold some honey to a few local businesses and gave a lot to friends and neighbors. When I talked to him he had lost more than ten of his colonies and told me about the parasites and pathogens that can kill the bees. But he also knew the remedies which could restore their health, because he cares about his bees.

First, I learned, there is the Varroa destructor, or varroa mite, a parasitic mite that attaches itself to a bee and feeds on it – sucking out its storage of fatty acids, glucose, and other energy sources. Besides weakening the bee, the open wound exposes it to virus infections, which further debilitates the insect, leading to deformed wings. Once the Varroa mite is in an area, every hive is going to get infected.

Beekeepers can get rid of the mites by using oxalic acid, an organic compound. They put crystals of oxalic acid in a little tray inside the hive, attached to a 12 volt battery. When heat is applied via the battery it sublimates, meaning that it converts from crystals to smoke. It literally becomes smoke inside of the hive which kills the little mites, but it does not affect the honeybees. This is done in October, and for a second time three weeks later. This treatment reduces the number of mites dramatically, and the hives will make it through the winter.

Then there is American foulbrood and European foulbrood; bacterial diseases which are so infectious that some countries require all infected hives and equipment to be destroyed. And there is chalkbrood disease, which is caused by a fungus. It affects the bee larvae which ingest the spores of the fungus which then look like little pieces of chalk, or tiny mummies. The spores grow mycelia, a tiny network of filaments which steal the nutrients from the baby bee, eventually killing it and forming a hardened mass around it. Luckily it usually isn't a serious disease because it can be prevented with good ventilation and adequate warmth.

Colony collapse is the worst that can happen. My beekeeper friend explained: “It followed right after the mites. You go into the hive in the spring after winter, and there's absolutely not a dead bee around. There are no bees. Well, where did they go?”

“Earlier, we saw a telltale sign of this symptom: we would find bees on the ground, just out in the field, and they're going around and around in a little circle. They seemed confused, disoriented. And then they don’t find their way back to their hive, and they die somewhere outside”. How sad, when you consider that every worker bee wants to fulfill her duties: take care of the queen, feed the babies, forage for nectar.

“Colony collapse, we think, is due to a pesticide that was first developed by Monsanto (now owned by Bayer, one of the largest pharmaceutical and biomedical companies in the world): a neonicotinoid (“neonic”). We think it affects the minds of the baby bees. The bees come out to forage, they're going to eat the nectar. And this product is in the nectar. It's in the pollen that they feed to their little ones, and that's at the time when the cells are dividing rapidly, because they're in a tremendous growth period. This neonic, chemically similar to nicotine, affects them, and as an adult bee, they go in and out, they're foraging, but ultimately, it's like Alzheimer's. They can't find their way home, and there are no dead bees in the hive because they died somewhere out there”. Again – this sounds awfully sad!

I had to look up neonics. From what I could discover, the use of these insecticides is partially banned in Europe. According to Wikipedia, the Obama administration issued a blanket ban against the use of them on National Wildlife Refuges, in response to concerns about off-target effects of the pesticide and because of a lawsuit from environmental groups. In 2018, the Trump administration reversed this decision, but in May 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency revoked approval for a dozen pesticides containing clothianidin and thiamethoxam as part of a legal settlement. But I couldn’t find any info about a blanket ban of neonics in the U.S. Some states try to prohibit their use but face resistance from commercial agriculture and — surprise! — the pest control industry.

Monotype crops also have a negative impact on pollinators. In Indiana, for example, one only sees corn. Monocrops have shorter bloom times, which means that nectar and pollen are only available for a short time. Also, research has shown that bee populations in such areas are more vulnerable to parasites. The lack of diversity weakens their immune systems.

We humans change the natural process of things at our own peril, it seems. Besides bees, other insects like moths and butterflies are affected by pesticides. The caterpillar of the Monarch butterfly feeds on the leaves of milkweed which often grows near cultivated fields. The wind carries the neonics over to the milkweed which the Monarch caterpillar eats, with the result that over the last two decades the numbers of Monarchs have declined by about 80%. And it goes on: birds are starving because they can’t find enough insects to eat.

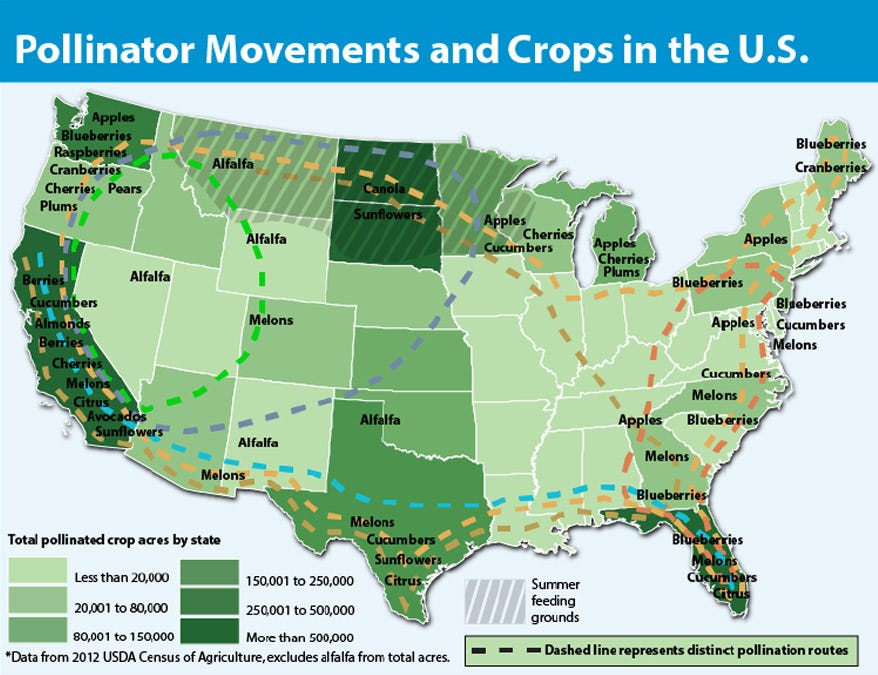

To pesticides, pathogens, and monocrops I want to add a relatively new abomination which kills bees, namely industrial bee farming. In California, for example, the multibillion dollar almond industry requires that over two million colonies have to be transported over vast distances, sometimes more than 2,000 miles, and sometimes more than once a year, in order to ensure pollination. No bees — no almonds, so all those hives are boxed up and loaded onto diesel trucks.

When I look at the images I’m including here, I’m quite certain that any exits for the bees are closed, otherwise one would see some swarming around. Now imagine how much these trucks constantly shake and vibrate when driven, and how loud the engine noise of the truck and all the other vehicles on the road would be. It doesn’t take much to understand how absolutely horrible this must be for the bees! The stress easily makes them sick and vulnerable.

When you google “commercial beekeeping”, you’ll find lots of websites that will teach you how to make money with a beekeeping business. They all promise that it is profitable, that it doesn’t need much money to start, and that it is a fast-growing industry. Maybe that’s why the number of honeybee colonies in the U.S. was at a record high in 2024, at 3.8 million; again, the California almond industry is the driving factor. But this is a misleading number, because over 62% of these colonies are lost, the bees have died. Project Apis m., the nonprofit mentioned above, did a survey to assess the extent of the 2025 colony loss; they gathered data from 702 respondents, about 68% of the nation’s commercial beekeepers. The result of the survey revealed some shocking numbers: “... [R]espondents directly lost an estimated $224.8 million in colonies alone. This is based on $200 per colony, a conservative replacement cost that does not include the value of labor, feed, and treatments to maintain them…[leading to] a total of $634.7 million in lost colonies. Lost income from almond pollination is estimated to exceed $428 million as valued at 2023 hive rental fees which averaged at $181 per colony.”

Some of these commercial beekeepers are going out of business altogether. Do I feel sorry for them? Of course, when I think of them as individuals with families who face hardships. But what happened to all the bees — that hurts more.

Thanks for a loving tribute to one of my favorite creatures.

Thanks, Wes -- good to know you love them too.