Maybe I’m stepping out on a limb here. Maybe none of my readers are interested in Who or What. But I’m on a roll – I want to stress the need for a drastic change in human thinking and perception in the face of weather extremes and climate breakdown. When I turned vegetarian/vegan it was first of all because of the immense suffering the meat and dairy industries are causing non-human animals. The obvious health benefits that I noticed right away were only secondary. However, over the last few years the rising temperatures in the arctic and antarctic regions as well as of the ocean waters have added an urgency that gets stronger by the minute. And yet – life goes on as usual.

I grew up in Germany, and the climate change there is startling to me. When I was a kid the summers were rather dismal. Most of the time it was grey and/or raining. The days of sunshine could be counted on one hand, and if on rare occasions temperatures reached 30°C (86°F), we didn’t have to go to school because it was too hot (summer vacation was only for four weeks, in July or August, making a rare hot school day possible). I left Germany for good early in 1973.

Over the last 20 years or so the weather in Germany has changed dramatically. They have tornadoes, hurricane-like winds which have uprooted tens of thousands of trees, floods that washed away whole villages, and 30°C (86°F) in the summer is the new normal. Temperatures can, and frequently do, climb much higher.

There are many locations in the U.S. with increasingly extreme weather patterns, but I’ve lived in northern New Mexico for the last 23 years, and the fluctuations haven’t been quite so excessive there. So, my personal and entirely anecdotal experience is based on conversations with people in Germany – and what I hear makes me nervous.

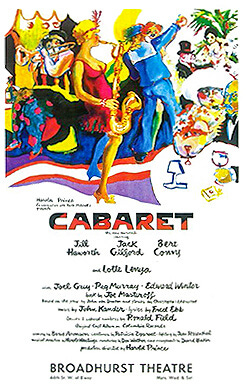

Alright, back to the topic of this week’s post: Christopher Isherwood, who in his collection of essays about Vedanta, The Wishing Tree, shared what he thought after he had been introduced to the teachings: “Why didn’t somebody ever tell me so before?” But not so fast: it occurred to me that people born after 1975 and possibly earlier have no idea who Christopher Isherwood is. You may know about the musical Cabaret – it has been playing on Broadway on and off since November 1966. It can currently be seen at the August Wilson Theatre and received nine Tony Award nominations for 2024. And you may even have heard of the movie by the same name, starring Liza Minelli, which won eight Oscars. It was released in 1972, so I’m not sure…

Both the musical and the film are based on stories written by British playwright, novelist, and screenwriter Christopher Isherwood. He was born in 1904 in Cheshire, England and lived in Berlin/Germany from 1929 and 1933 – attracted by the city’s openly gay subculture which flourished in the era between World War I and the rise of Nazism. Based on diary entries, a habit he kept up all his life, he published Goodbye to Berlin, a semi-autobiographical account of his adventures in the city which was the heart of Germany’s cultural life. A thriving center of music, theater, visual arts, and literature, with a seedy underworld that tolerated hedonism and excess, Berlin was sizzling with tension and social contrasts. Devastating poverty next to frivolous luxury, a bohemian lifestyle next to rising fascism and its philistine values, resulted in an atmosphere of unfettered and quite desperate lust for living.

Because Hitler’s Nazis kept gaining strength in Berlin, Isherwood left Germany in 1933, and in 1939 he emigrated to the United States where he met many other European expatriates who were fleeing fascism. Among them was Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World (1932), another book I’m not sure young people are familiar with. He also wrote Doors of Perception which was published in 1954, an account of his experience with peyote (mescaline).

The Huxley home in the Hollywood Hills was a hotspot for west coast avant-garde and attracted luminaries [sic] as Orson Welles, Igor Stravinsky, George Cukor and Christopher Isherwood. (Huxley on Huxley)

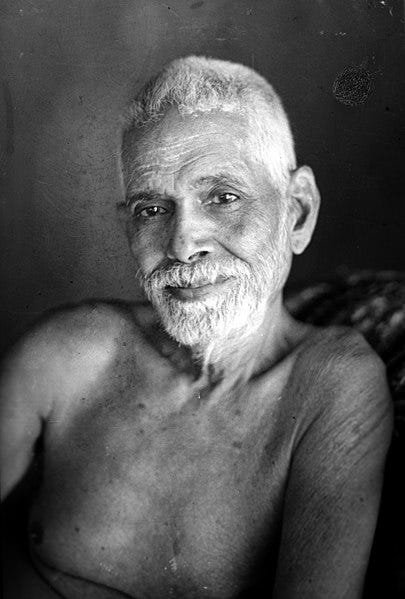

It was Huxley who introduced Isherwood to Vedanta, after they both met and became friends while living near Los Angeles. The Vedanta Society of Southern California, founded by Swami Prabhavananda, a monk of the Ramakrishna lineage, became the focal point of Isherwood’s life for the next 35 years.

And finally we’re getting to Vedanta. Below is my entirely personal interpretation. I’m not a practitioner, I never had a guru, and Vedanta is but one of several philosophies and thought systems which have influenced the way in which I think and feel about the world. In particular, I’ll talk about Advaita Vedanta, usually translated with non-dual Vedanta, or better non-secondary. In a nutshell, it confirms what this Substack is about: everything is connected, there’s only ONE. Including the universe.

Vedanta’s teachings unfold this one-ness quite logically. In normal waking consciousness, our mind is constantly filled with sense perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. My understanding of who I am is determined by these ever changing, fleeting attributes: I am a mother, a writer, a woman; I am tall or short, fat or thin, kind or distant; I am a lawyer or a chimney sweep; in other words, I am an infinite parade of inconsistent and often contradictory qualities. My concept of self is determined by the flow of perceptions constantly streaming in. But when I sit quietly and step by step relax the body and the mind, it becomes possible to differentiate between the many half-conscious feelings and assumptions which form the inextricable knot of our normal identity. One discovers the distinction between the witnessing presence and the witnessed perceptions. To use an analogy, it is as if you would suddenly find yourself on a stage, playing a particular role, whereas before, you took the play for reality.

One aspect of Vedanta which I especially enjoy is its use of analogies. Take a red hot iron ball, for example: it illuminates the state of our mind better than 1000 words. The qualities of the red hot iron ball are completely fused; to be what it is, not one of them can be left out or taken away. And yet, we can know its different components, we can differentiate and distinguish. Similarly, we can learn to recognize the seer and the seen, the subject and the object, the body, the mind, and the ever-present awareness.

Oh human, know thyself -- this inscription at the site of the Delphi oracle seems to be the fundamental postulate of all true wisdom teachings. The knowledge referred to is not limited to a psychological interpretation; it does not relate to subconscious, personal issues, although an understanding of one’s shadow sides is certainly necessary for a healthy mind.

While religions demand faith in the doctrine revealed by the Gods or God, Vedanta starts with what we most intimately know: ourselves. A closer look will show that we actually do not know ourselves, but this is due to ignorance. The Self is intrinsically knowable because it is always there.

The claim of Vedanta that there is only one truth, that this truth can be known, and that it is in fact knowledge of one’s Self, may at first seem radical. However, its reasoning is convincing and sound, if one is willing to follow the subtle and complex unfolding. Easily enough, it starts with what the Self is not. I, the subject, see the chair, an object -- clearly, I am not the chair, I am not an object. If this seems ridiculously obvious, it soon becomes less so when I look at my hand or my foot, when I consider my body. Clearly I am not my hand or my foot; neither am I the totality of my body, because I can name it as an object. It shares the characteristics of all other objects: it has a beginning and an end, it is impermanent and changes. At the same time, though, I notice that I identify with my body since almost all experiences seem connected with it. What about my sense organs, like sight, hearing and touch? I need them in order to perceive my physical body; might they not be essential to me? This may at first look reasonable, but upon closer inspection I have to admit that I am not my sense of vision or of smell, any more than I am my eyes or nose. All the sense organs can be objectified, as can be my feelings, my moods, and my thoughts, including the I-thought, or ego. My mind is not who I am. Thoughts and feelings change, they come and go, they are known. What is known cannot also be the knower; what is seen cannot equally be the seer. This leaves me as the knower and the seer, or better, it leaves “me”. I am the unchanging presence, the silent witness, the pure awareness, constant, unlimited, and eternal. I am the light of consciousness that illuminates the mind and the world.

Once we learn to differentiate the mind from the consciousness that underlies it, we recognize it -- the mind -- as another object that is “not-me”. The mind in its ignorance mistakes itself to be consciousness, but every mood, thought, and emotion is known, or witnessed, by my Self. The one who knows, the subject, “me”, is pure consciousness which is identical with pure being. For the purpose of knowledge, differentiation between body, mind, sense organs, thoughts, feelings, etc. and the ever-present unchanging substratum of pure awareness is a necessary process. But the fundamental and absolute reality is essentially non-dual, advaita, beyond subject and object. What is more, since there is only one consciousness, it is the same for all people, for all individual minds; for all beings, actually.

This is difficult to grasp for the contemporary Western mind, so geared toward individualism. Would not my sense of Self be lost like a drop of water in the ocean, if billions of people share the same self? How can I still be “me” if I am mixed in with everybody else? But when you really think about it: this feeling of being uniquely “me” belongs intrinsically to consciousness, not to the mind or the body. Since mind and body are superimposed on and wrongly identified with the Self, I assume that it is my personal identity which distinguishes me as a Self, as a conscious being. While I may feel uniquely “me” because I am a woman and have this or that talent, this or that particular character, I am also -- apparently -- extremely limited. My body will sooner or later die. However, if the feeling of being present, the certainty that I am, belongs to consciousness and not to the body or the mind, then this feeling could not possibly diminish, with or without a body.

The analogy of the red-hot iron ball makes this clear: the iron object and the heat are two distinct elements which are experienced together, as one. Likewise, the form of the ball is superimposed on the substance, the iron. When I superimpose the Self onto the mind and physical body, I “am” a woman, a child, a mother, etc. In reality I am none of these distinctions and limitations; I am the fullness, wholeness, totality.

There is only one consciousness. It shines on the various experiences of the individual, but remains forever the same clear light. Liberating the individual Self from the bondage of ignorance is one of the foremost goals of the Vedanta teachings. There is only one reality, one truth, one Self, one pure awareness. To mistake one’s identity for a separate, discrete entity is due to the identification with the body and the mind which in turn is based on ignorance. The Self is forever free, unlimited, infinite, eternal, divine.

One has to realize that the black-and-white reality of the physical world is not absolute. Questioning who I am, I have to learn to detach myself from the immediate and definite answers the world constantly offers. I have to recognize that the roles I play are like coats, to wear and to take off. Just as clouds may hide the sun from my view but do not in any way affect or alter its brilliant light, so does ignorance obscure the knowledge of the Self, without being able to influence its nature.

While I can’t be sure that the teachings of Advaita Vedanta are the truth, they make a lot of sense. They form a good basis from where to look at the world, myself, and everything else in it. Intuitively, it feels right. It helps me to treat other beings more kindly and to change habits that harm the Earth.

I do love the mystical quality of it. The hot iron ball is such an interesting idea.

Good stuff. Agree with your hot ball analogy.

Nice visual that. Thanks for ONE lovely Lunar Lammas Blessing.

♎🕯️🙏🌕 ♒