It’s hard for me these days to focus on anything but the broad attack on our democracy which unfolds every day. I grew up in the aftermath of Hitler’s Nazis and a fascist regime. It took the Germans a while to look at what happened and to face the devastating results. My parents’ generation was literally shell shocked and couldn’t really face the recent past. Questions about the Holocaust – “How could you let this happen?” – were mostly answered with “We didn’t know about it”. While this was absolutely unacceptable when I was a teenager, I am shocked to see something similar develop before my eyes.

The post-war German government did one thing right: anything related to Hitler and the Nazis was “verboten”. Illegal. I just checked: giving the Nazi salute in Germany can result in a six-months prison sentence. It’s NOT free speech. Musk should be in jail, not in the U.S. government.

But to get all frazzled because of the current political climate doesn’t help either. I have very thin skin, both literally and figuratively, and I have little protection against other beings’ pain, loud noises, people’s energy – I soak it up as if I were a sponge. It’s uncomfortable these days. And yet, it doesn’t help anybody and doesn’t change anything.

So, instead of writing about Project 2025 and its roots in the Lewis Powell Memorandum from 1971 as well as criminal presidents such as Nixon and Reagan, I’ll write about spiders. I love them, and a reader left a comment not so long ago admiring their intelligence. I wanted to find out more.

Forget about brain size. Even among humans, there’s only a very small correlation between brain size and intelligence. Other factors such as the complexity of synapses or neural connections are more important than size. When neurons can travel efficiently across this network, problem-solving and information processing are enhanced. If size were a major factor, spiders couldn’t be very smart – their brains are significantly smaller than the size of a pin. And yet, as we’ll see, they perform quite remarkable feats of problem-solving, have good memory, and develop smart strategies for hunting their prey.

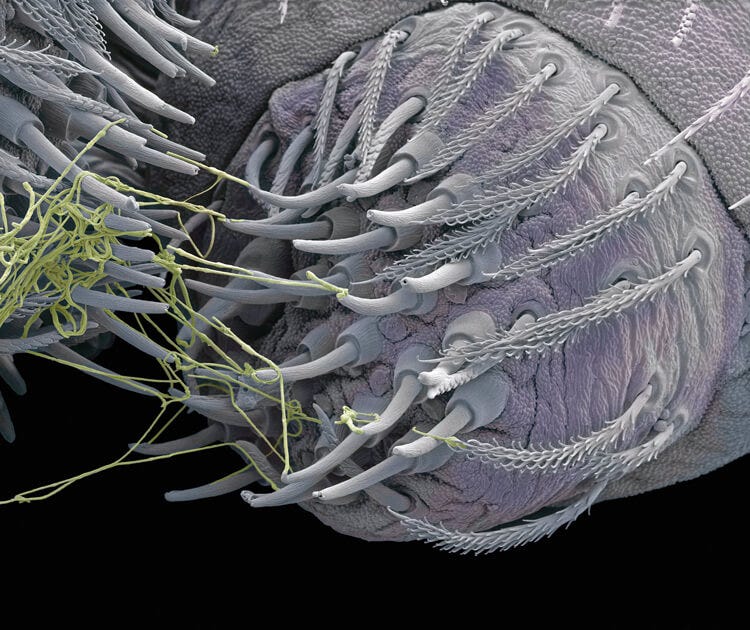

First, some general facts about spiders: they are arthropods, just like lobsters, crabs, millipedes, insects and mites, but they’re NOT insects but arachnids: they have eight legs, no antennae, no wings, and four pairs of eyes. Biologists have identified close to 50,000 different species of spiders! If you suffer from arachnophobia, the fear of spiders, you should settle in Antarctica, the only place on earth where these creatures don’t live.

Spiders vary greatly in size, from the Samoan moss spider, the smallest arachnid not bigger than one third of a millimeter, to the Goliath birdeater which belongs to the tarantula family and has a leg span of up to 30 centimeters (12 inches) – about the size of a dinner plate. One has an eensie-weensie brain, and the birdeater (they rarely eat birds, according to Wikipedia which also notes that humans in northeastern South America eat birdeaters. And humans all over the world eat birds; just sayin’ ) … the Goliath birdeater has a brain which must be over 1,000 times larger than that of the Samoan moss spider. And yet, they perform similarly sophisticated and complicated tasks. Researchers have tested both large and tiny spiders and found out that their skills and problem-solving abilities were about the same. They found that smaller beings – not only spiders, but also salamanders, hummingbirds, even humans – developed all kinds of strategies, still mostly mysterious to scientists, to do more with less (they managed to shrink their brains without losing their efficiency). If you want to learn more about brain size and intelligence, read this Scientific American article.

Let’s look at some of the complex things spiders are capable of.

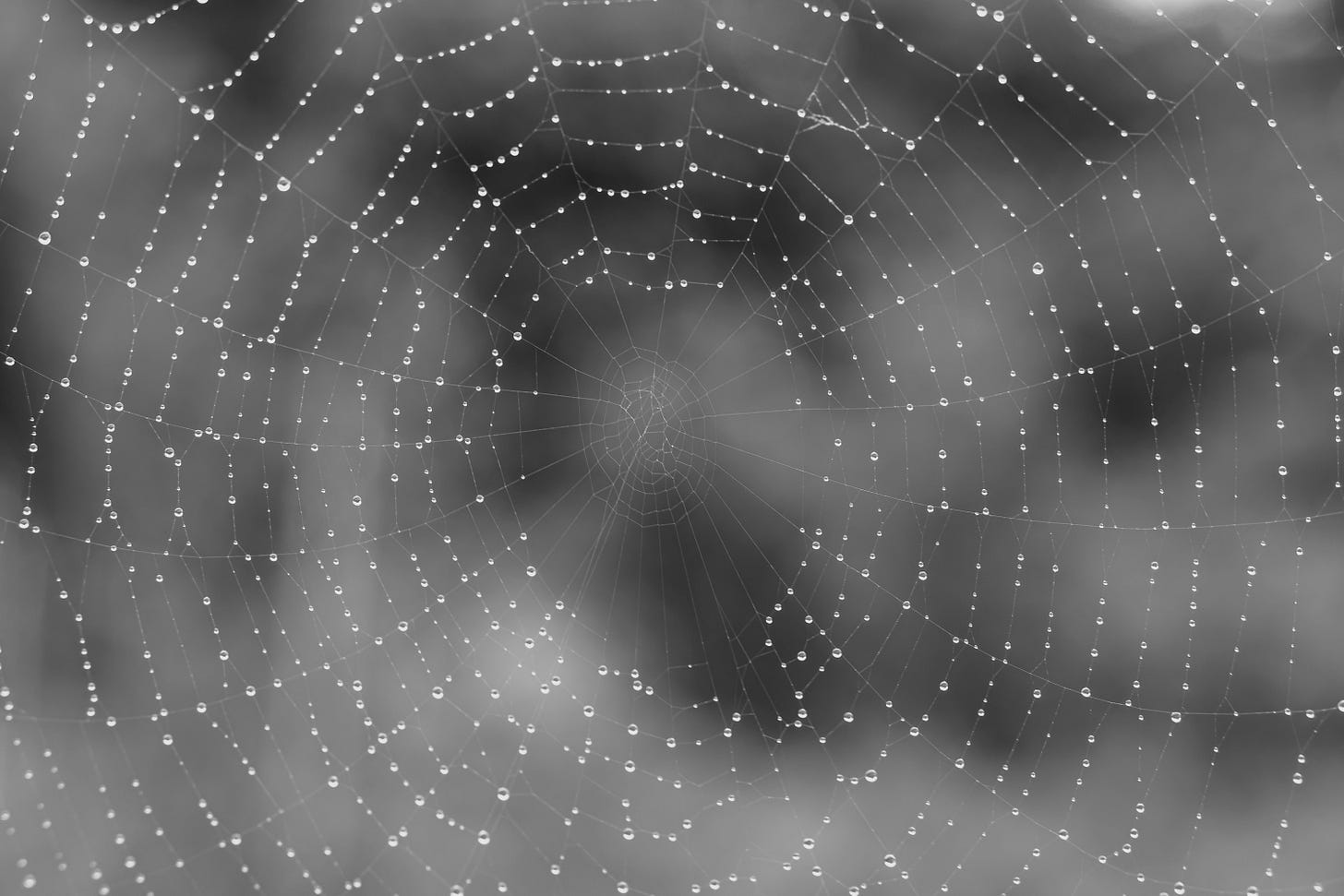

The beautiful webs and orbs come to mind first. I bet even people who are afraid of spiders will delight in these stunning creations! But there’s much more to them besides their visual appeal. A New Science article by David Robson, a science writer, explains in detail all the decisions a spider has to make while weaving a web. The article is behind a paywall, so I’ll list a few items from Robson’s essay.

WHERE to build a web requires individual decision making: orb webs “hold more secrets than Charlotte’s Web, because each is a record of the decisions taken during its construction,” Robson writes. Each spider has their own preferred size and shape of web, depending on its size and on its prey. But that ideal often is impossible because of obstacles or restricted spaces. The spider has to develop some sort of building plan, a mental representation of the future web. That’s a skill which scientists have documented in mammals and birds, but not among invertebrates, and is proof of the surprising intelligence of spiders.

HOW they maintain their webs after they’ve been built also demonstrates high cognitive capacities. In web areas where they have previously caught prey, spiders will adjust the tension of the strand because this enhances the vibration from a struggling insect and the spider can react more quickly. And when a prey hit the spider’s web but got away, the spider would produce silk strands that were more sticky, to prevent this from happening again. Smart indeed!

The spiders’ use of silk strands is remarkable as well. While the larvae of silkworms enclose themselves in a cocoon when they change into pupae, and while some ants make nests from silk, spiders produce silk strands for a number of reasons. Besides spinning their webs, they use them to protect their eggs. And the diving bell spiders collect large air bubbles which they take underwater and secure with silk threads. These “diving bells” allow the spiders to spend almost their entire lives under water.

Different species of orb weavers developed different kinds of webs, depending on their prey. As insects managed to escape the silky traps, spiders found new ways to catch their victims. When the triangle spider, for example, detects a potential prey, it releases a portion of the web which then traps the insect, like a collapsing tent.

The smartest spiders known to scientists are tiny jumping spiders, in particular the genus Portia. Most of them don’t build webs themselves, but they love to eat spiders who do build webs, although they might be 200% larger than they are! Even Portia’s looks is a ruse: some resemble a piece of dried-up leaf caught in the web. Orb weavers don’t have good eyesight, so they’ll move closer to clean up their web, only to become dinner before they know what happened.

Another of Portia’s hunting strategies is to shake the whole web of a potential victim to mimic a wind gust. This hides the vibration of its own movement as it closes in on the resident spider, attacks, and eats it. Scientists designed laboratory experiments which demonstrated that Portia can map out complicated routes in order to reach their prey, that they form a mental representation of their prey, and even that they can distinguish between one and two as discrete number categories, while larger quantities, three and higher, were only perceived as “many”. This is a similar sense for number quantities as one-year-old children have – quite an achievement for such a tiny creature!

Aren’t they magnificent beings? And yet, spiders elicit the most fear and disgust, according to psychological studies. Most of them not only are NOT dangerous, but beneficial, actually: they feed on aphids, flies, roaches, fleas, mosquitoes and other insects that destroy farmland crops, carry diseases, and are considered household pests. ONE spider can eat up to 2,000 insects a year, and we humans should be grateful – without them, our food supply would be seriously threatened.

Thanks for the lovely story about spiders. It's nice to hear from someone who is kind to creatures that most people abhor.

Here's my spider story:

For a while, every time I played my piano, this spider that was the size of a hand and flush-colored would come out from under my sofa and I swear, it would dance. It was like the Adam's family. When the weather got warmer, I booted it outside by putting a bowl over it, sliding a piece of cardboard underneath, and slowly pushing it out the door. From inside, I watched it walk away. And believe it or not, the next time I played the piano, I missed it.

Our NM home was a critter magnet. I did a short video when a tarantula ranged through.