A Snail In Shining Armor,

a.k.a Scaly-foot gastropod, Iron-shelled sea snail, or Sea-pangolin.

If you’ve never heard of these extraordinary creatures, it is because they have been only recently discovered, in April 2001. They live in the Indian Ocean at depths of about 1.5 to 1.8 miles (about 8,000 feet), and had been quite safe from human intervention until ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) had been developed, especially for the exploration of the deep sea.

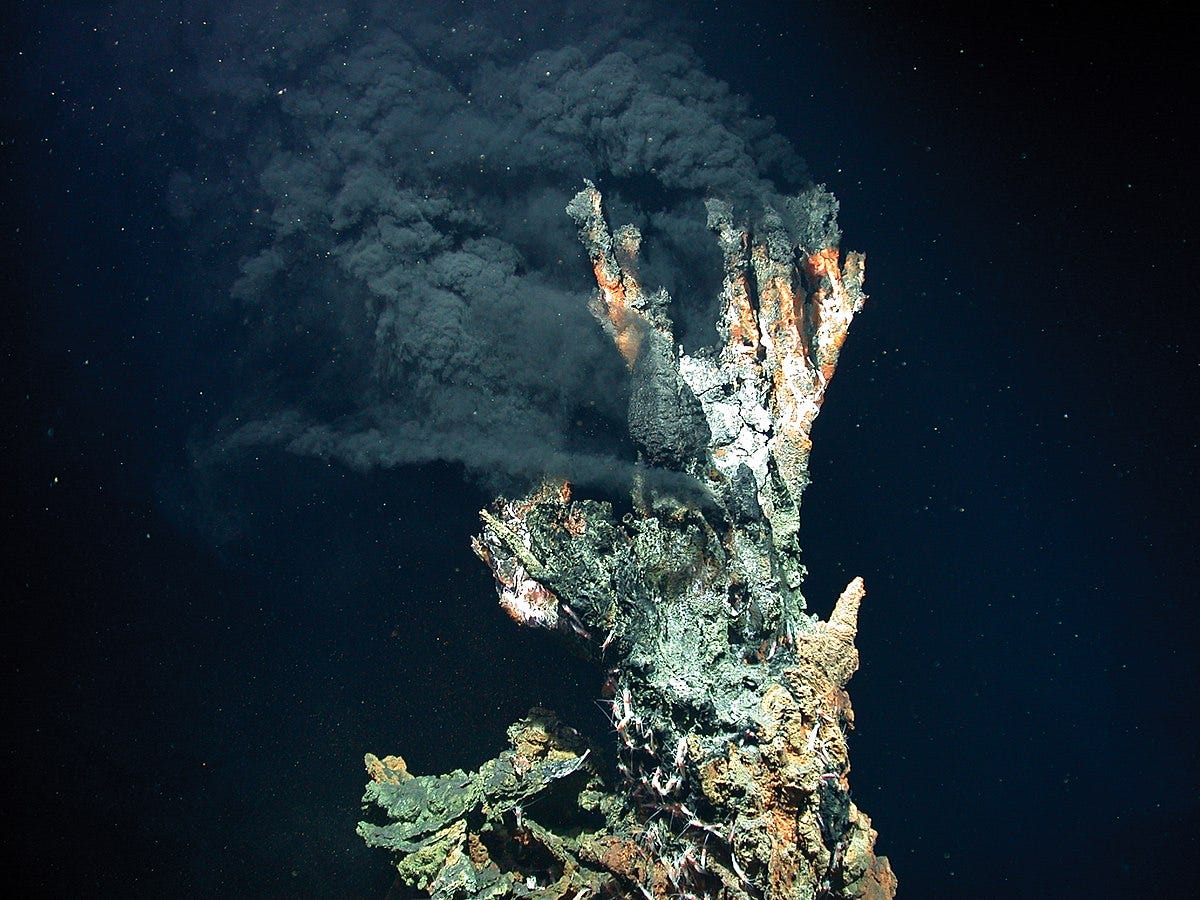

ROVs can safely go to and operate at depths which are inaccessible to human divers, and they can stay for a long time. In 2000, one of these, the Japanese ROV Kaikō, discovered the Kairei vent field – a hydrothermal vent located in the western Indian Ocean at a depth of 8,070 feet. It belongs to the Central Indian Ridge: a volcanic area which dates back 38 million years, when two tectonic plateaus separated and created fissures in the sea bed. Hot water from the earth crust below and mixed with rocks and mineral ore continues to escape through the fissures, like deep-sea ‘hot springs, and the deposits form chimney-like structures called smokers. The plumes of heated-water discharges are either dark or light, and there are black smokers – black, chimney-like structures that emit a cloud of black material – and white smokers, with vents which emit lighter minerals and particles.

While the temperature near the ocean floor at such depths is around 36 - 39 °F (2 - 4 °C ), the fluids from the vents can be higher than 680 °F (360 °C ). And not far away, in a transitional zone between the extreme heat and the cold sea bottom, a number of creatures live in a hydrothermal vent community. Within the Karai vent field, about 35 different species have been discovered so far, among them the scaly-foot gastropod (Chrysomallon squamiferum) – first detected in 2001 by the ROV Jason during an expedition by the U.S. research vessel Knorr. Later, two other vent fields were found where the species live: the Solitaire field, and the Longqi vent field.

Another name of Chrysomallon squamiferum Is Volcano Snail, because it lives near these hydrothermal vents where the temperature can reach up to 750 °F. In order to protect itself from extreme underwater pressure and high temperatures this little animal (the only known gastropod with a suit of scale armor) forms a shell of iron sulphide which has three layers: the outer one consists mainly of iron sulphides, and is even magnetic! The middle layer is equivalent to the periostracum, the outermost layer of snails and clams and other gastropods. It may serve as protection from harsh corrosive marine environments or absorb mechanical strain, but scientists aren’t certain what it’s for – except that it helps to dissipate heat. The innermost layer is made of aragonite, a mineral that forms naturally in almost all mollusk shells, for example clams, squids, and snails. Aragonite is also part of corals.

Something else is unique about the iron-shelled sea snail: its foot, which has hundreds of dermal scales covering its exterior surface. Just like the shell, these extensions have an outer layer made of iron sulfides. There is no other known animal on Earth with mineralized structures on its foot.

But that’s not all. This little snail has a large and well developed heart which is approximately 4 % of its body volume, the largest heart relative to body size in the entire animal kingdom! It allows the snail to live in an environment that’s largely devoid of oxygen.

And there’s more! The sea pangolin is also a holobiont, the symbiotic cluster formed by a host and other species living around it, all of which create a unit. The snail is the host for countless bacteria which live in a large gland of its digestive system. They produce energy for the snail which provides the bacteria with oxygen and hydrogen sulfide. Which means that scaly-foot gastropods don’t really eat anything… truly peculiar creatures.

Other odd and unusual marine animals have been discovered living around deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Unfortunately for them, they’re now threatened by extinction – like so many other life forms after they come in contact with humans. The little iron-shelled snails are in danger of being obliterated by deep sea mining. Minerals such as copper, silver, gold, nickel, and cobalt which can be found on the ocean floor near the vents are prime targets for underwater mining operations.

The International Seabed Authority, an intergovernmental organization with 167 member states which is part of the United Nations, was formed in 1994 with the objective to authorize and control deep sea mining. According to a United Nations General Assembly resolution from 1970, the deep seabed and ocean floor belong to the Common Heritage of Humanity and should be preserved for peaceful purposes. A recent Council meeting of ISA members concluded in March of 2025 that permits for commercial deep sea mining can’t be issued before further studies have been implemented. Not surprisingly, The Metals Company, a public company that produces base metals from polymetallic nodules, decided to sidestep the ISA and plans to apply for permits for deep sea mining under an existing U.S. Mining Code in the second quarter of 2025. TMC (The Metals Company)’s CEO Gerard Barron stated that “Trump is the best news for deep sea mining”... enough said.

Our little snail in shining armor was put on the Endangered Species List in 2019. Will they survive human greed? I’m not holding my breath.

What a truly extraordinary little creature. Thanks Jessica. Have you ever seen the asknature.org site? Then there's the biomimicry.org, both sites my son loves.