In the realm of cephalopods, the octopus definitely is the star. They’re incredibly photogenic, changing their colors and shapes to resemble rocks, corals, and seaweed. Some in captivity became famous because of their intelligent antics: Inky, the Escape Artist, or Otto who learned how to turn off the lights in his aquarium at night. And then there is My Octopus Teacher, an award-winning documentary, plus some popular books such as The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgommery. With all this attention, no wonder that other members of the cephalopod family look like poor cousins, and the nautilus ranks pretty close to the very bottom.

Not as far as their “usefulness” for humans is concerned: the nautilus’s pretty shell has been used or rather exploited ever since the Renaissance. Look at the gilded salt cellar above, called the Burghley Nef, which was crafted in Paris around 1520. The hull of the ship was made from a nautilus shell and could hold salt or spices. The cup below originates in 16th-century Germany. Nowadays the iridescent material of a nautilus shell is being used for relatively cheap jewelry and has depleted the number of animals to such an extent that scientists are quite worried.

More about this later on; first, let’s look at the creatures themselves.

Nautiluses have existed for more than 500 million years and belong to Earth’s oldest true animals. They’re often considered “living fossils”, which means that they haven’t changed much in appearance during all this time, although there used to be much bigger species which have gone extinct by now (while prehistoric nautiluses had shells that could be ten feet long, the species existing today measure only up to ten inches).

Several characteristics distinguish the nautiluses from their cousins: the octopuses, squids, and cuttlefish. The protective shell is the most obvious difference, but there are many others. While the other cephalopods have sophisticated eyes similar to vertebrates, for example, the nautiluses have an eye structure without a solid lens. It’s similar to a pinhole camera and creates only simple images. But they have two pairs of ocular tentacles located in front and behind the eyes which are sensory organs. What they lack in seeing capacity nautiluses make up with an acute sense of smell. The ocular tentacles can detect odor and are able to determine how far the odor comes from.

They have a lot more tentacles than other cephalopods, up to 90, and they are different from the arms of an octopus or squid or cuttlefish. The tentacles don’t have any suction cups but produce some kind of glue that allows the nautilus to grab food and hold onto rocks.

While octopuses, squids, and cuttlefish are relatively short-lived – they live for three to five years at most, many only for one year – a nautilus can reach 20 years, and some have been known to live for 30 years. The female lays about a dozen eggs, which are attached to the walls of her shell. They take almost one year to develop! When the babies hatch, they are little more than one inch long.

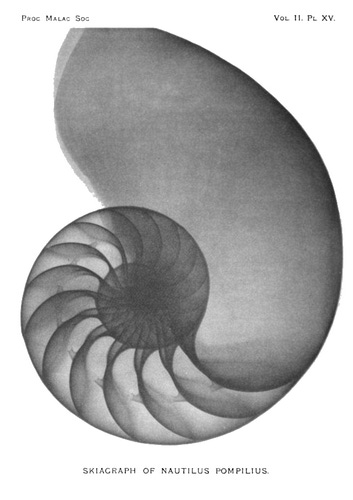

No other cephalopod besides the nautilus has a chambered, external spiral shell. It forms as the animal grows; the body is located in the largest, outermost chamber. When this becomes too tight, the animal seals it off and makes a new chamber. The walls separating the chambers are called septa. They’re all connected by a thin strand of nerves and blood vessels, the siphuncle, a clever evolutionary function which allows the nautilus to control its buoyancy. The chambers contain both air and water, and the siphuncle allows the animal to control the amount of each, which means it can go up or down at will. When a baby nautilus hatches, its shell has four chambers. As an adult, the shell has grown to 30 or more.

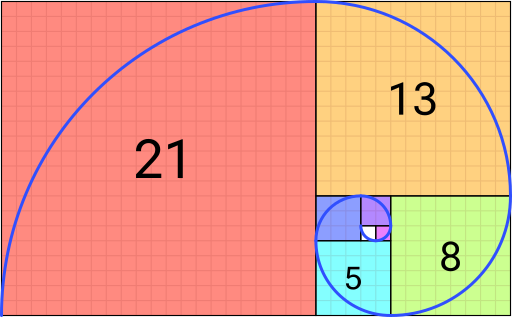

I find the beautiful spiral which a half-shell makes visible most fascinating. It was long considered to be a golden spiral, based on the golden ratio: represented by the Greek letter Phi (φ or ϕ), it describes a rectangle with long side a + b and short side a which can be divided into two pieces: a similar golden rectangle (shaded pink, above right) with long side a and short side b and a square (shaded blue, above left) with sides of length a. Or a + b is to a as a is to b. As a decimal, it is an irrational number 1.618033988749.... which means that it can’t be reduced to a whole number, it goes on into infinity!

The Golden Ratio, in turn, is closely related to the Fibonacci sequence, an ordered list of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers. Starting with 0 and 1, it goes 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, … again to infinity. Although the Fibonacci sequence was already written up in the Indian Vedas between 450 BC and 200 BC, it first appeared in Europe in a book about rabbit population, Liber Abaci, written in 1202 AD by the Italian mathematician Leonardo Bonacci or Leonardo of Pisa who became known as Fibonacci – short for filius Bonacci or “son of Bonacci”.

In nature, countless plants grow with a pattern following the Fibonacci sequence: sunflowers, pinecones, branches on trees, petals of daisies and many more. For a long time, the nautilus shell was considered an example of the Golden Ratio. In the 1990s I read Robert Lawlor’s book Sacred Geometry from 1989, where he writes “The Golden Mean spiral, in which the geometric increase of the radial arms is equal to ϕ, is found in nature in the beautiful conch shell Nautilus pompilius [Chambered Nautilus]...” However, the math doesn’t quite match and the spiral is more correctly called a logarithmic spiral, which means that the distances between the turns of the spiral are constant. The turns of a spiral based on the Golden Ratio grow progressively. Either way, isn’t it marvelous that galaxies and the horns of bighorn sheep and sea shells and aloe plants all grow with consistent patterns that can be expressed with mathematical formulas?

One more thing: please don’t buy products made of a nautilus shell. These include the shells themselves and jewelry made from them. Because of their iridescence they’re even made into fake pearls – Osmeña pearls – which can sell for thousands of dollars, according to this New York Times article. Nautilus populations are declining and they have been added to Appendix II of CITES, a multinational treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of international trade.

That was just so fascinating! Thank you Jessica for making it so readable.

This was extremely interesting. I never really considered nautiluses, but now I'm very curious...and irritated their population is dwindling... And I can't believe I used to enjoy eating octopuses—they are magnificent creatures that should be appreciated far more.